Effect of Motivational Type on Goal-Setting Behavior

Maryam Kazmi

Boston College

Abstract

Whether an athlete is intrinsically, extrinsically, or amotivated and whether or not he or she sets goals are important determinants of that athlete's performance. This study was aimed at exploring whether a certain type of motivation can predict whether a person will use goal-setting techniques and find them to be effective. The present study also hoped to determine whether the type of motivation that athletes reported and their goal-setting behavior differed depending on whether they were recreational or elite collegiate athletes. Male basketball players were recruited to participate in the study, half of whom were recreational athletes and the other half from the Boston College Men's D1 Basketball team. Through the use of two separate questionnaires that were administered to participants, the results of the studies supported the assertion that intrinsically motivated individuals tended to set more goals, commit to these goals, and found these goals to be more effective than those who exhibited the other types of motivation. No differences existed between the recreational group and the D1 group in either motivation or goal setting behavior. This study informs researchers that individuals who participate in a sport for the sake of the sport itself tend to set more goals in order to benefit their own performance.

Introduction

Many of us have participated in sports and are familiar with the types of behavior that are required of athletes, but have you ever wondered why some athletes are able to keep themselves more motivated than others? Why is it that only a few of the people we played sports with have continued to play in college and a fraction of that number play professionally? Researchers have looked into athlete behavior and determined that differences in goal-setting and motivational types appear to affect the manner in which one performs, by either enhancing or impairing performance. Motivation is an important issue that has been studied time and time again to determine the different sources of motivation and how effective they prove to be. Moreover, goal setting is a technique employed by various athletes, which can contribute to their overall performance. This study explores correlation between the two topics of motivation and goal setting.

Primarily, literature concerning motivation focuses on what forces drive a person to be motivated (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Motivation is defined as the impetus behind a person's actions; it affects why people act in certain ways, leading to the goals that they implement for themselves (Ryan & Deci, 2000). The reason that a person is motivated, or orientation of motivation, can be explained by Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Self-Determination Theory posits that a person can be extrinsically or intrinsically motivated (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Deci & Ryan, 1985). A cursory look into Self-Determination Theory supports that intrinsically motivated individuals tend to engage in an activity purely because it is enjoyable or interesting in itself (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Thus, the reward for doing this activity is the activity itself. On the other hand, someone who is extrinsically motivated participates in something due to an external outcome. Four different levels of extrinsic motivation are currently outlined, each varying in its degree of autonomy. These levels are, from least autonomous to most autonomous: external regulation, introjection, identification, and integration (Ryan & Deci, 2000). There is also a category known as amotivation, which defines a state in which a person is not moved to act at all.

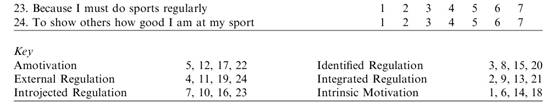

Past research has found that gradual progression from amotivation to extrinsic motivation and then to intrinsic motivation causes increasingly positive consequences for not only psychological functioning but also performance in sports. This is due to an increase in enjoyment and satisfaction of the sport as well as persistence and positive emotions (Pelletier, Fortier, Valler, & Tuson, 1995). In order to study the different types of motivation, an instrument that would assess an athlete's motivational type needed to be designed. A French scale, the l'Echelle de motivation dans les sports (EMS), was constructed initially and it was validated into an English version, known as the Sport Motivation Scale (Briere, Vallerand, Blais, & Pelletier, 1995; Pelletier et al., 1995). This scale originally designated seven subcategories of motivation: amotivation, external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, and three separate subsets of intrinsic motivation – to know, to accomplish, and to experience stimulation (Pelletier et al., 1995). However, following a revision of the original Self-Determination Theory, researchers altered the motivation continuum to include integrated regulation, which is the most self-determining form of extrinsic motivation (Mallett, Kawabata, Newcombe, Otero-Forero, & Jackson, 2007). Researchers also found that the three forms of intrinsic motivation previously classified were indistinguishable and thus were not necessary (Mallett et al., 2007). Accordingly, the modified Sport Motivation Scale-6 tests the six subcategories on the motivation continuum that Deci and Ryan (2000) outlined (Mallett et al., 2007; Ryan & Deci, 2000). This questionnaire (Appendix A) will be used to determine motivational types of athletes in the current study.

Additionally, goal setting is another area of study that is emphasized in the field of sport psychology. Previous research found that people who use goal setting tend to be more motivated and better adhere to their exercise routines (Brookfield & Wilson, 2009). Furthermore, there are certain kinds of goals that have proven to be more effective than others. Various researchers explored the differences in performance between those who set specific, detailed goals for themselves and those who set broader goals. In most studies, it has been shown that more specific goals tend to lead to more success in performance (Locke & Latham, 1985; Kane, Baltes, & Moss, 2001; Kleingeld, Mierlo, & Arends, 2011). Only in one study did this not hold true; specific goals did not produce significantly different results than goals in which athletes were simply told to do their best (Weinberg, Bruya, & Jackson, 1985). It is possible that there were confounding variables in this older experiment, and results similar to those of the more recent studies can be expected. Researchers also explored the phenomena that athletes' performance increased with increasing difficulty of the goals, but unrealistic goals caused a decrease in performance (Bar-Eli, Tenenbaum, Pie, Btesh, & Almog, 1997). Clearly, athletes must employ goal setting for optimal performance but need to have a realistic level of difficulty in these goals.

Further differences in goal setting occur due to the ends toward which the goals were directed. For instance, goals that address self-mastery and attempt to improve an individual's performance simply for the sake of improvement provide more successful results (Burton, Weinberg, Yukelson, & Weigand, 2013; Isoard-Gautheur, Guillet-Descas, & Duda, 2013). Athletes who employ this type of goal setting also experience less burnout at the elite level (Isoard-Gauther et al., 2013). Thus, this type of behavior would be expected more from collegiate athletes at the Division 1 level than the recreational level because they would have been less likely to burnout during high school. Studies have also found that goal setting causes less anxiety for recreational athletes but that these effects are less profound (Ryska, 1998). Most importantly, this type of goal setting that is focused on self-mastery is linked to higher levels of intrinsic motivation in athletes (Brookfield & Wilson, 2009; Weinberg, Yukelson, Burton, & Weigand, 1993). Athletes who are most successful at setting goals for themselves would be expected to be intrinsically rather than extrinsically motivated. Goal setting behavior can be determined by assessing the frequency and effectiveness of the goals as well as the athlete's commitment and effort (Weinberg et al., 1993).

Evidently, motivation and goal setting both affect an athlete's performance and seem to be inextricably linked. This study will contribute to the literature by determining whether a person's motivation type can predict goal setting behavior. Because researchers have already determined that goal setting is effective in improving performance, this study will address the question of why some people set more goals than others. The motivational types and goal-setting behaviors of Division 1 (D1) athletes will be compared to those of recreational athletes. I expect that athletes who are more intrinsically motivated will report using goal setting more often and find it more effective because they are using it to better themselves for the sake of improvement alone. Also, I would expect to find that this intrinsic motivation and effective goal setting behavior is more prevalent in D1 athletes because they need to be intrinsically motivated in order to decrease burn out and increase their performance at an advanced level.

Methods

The sample in this study was 27 male collegiate basketball players. There were 14 males who play D1 basketball for Boston College and 13 recreational athletes who do not play for the institution. It was ensured that the recreational athletes all played basketball at least twice a week in order to reduce variability among participants. The ages of the participants ranged from 19-22. Only males were chosen in the present study because it is difficult to find females who play basketball recreationally with the same frequency. This is also the reason that basketball was chosen as the designated sport; both D1 athletes and recreational athletes are readily available. Participants reported between 3-16 years of experience in the sport (M=10.85, SD=3.85) and reported their athletic ability compared to the best athletes they play against on a scale from 1-9 (M=4.85, SD=2.1). Although the skill level varied among participants, it had no effect on the data being collected concerning motivational types or goal setting behavior.

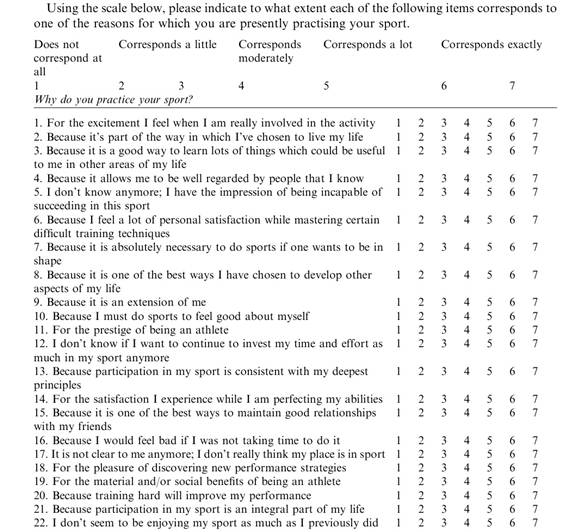

In this study, motivational type was the independent variable. Using the Sport Motivation Scale-6 (SMS-6, Appendix A), athletes were scored on six categories: amotivation, external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, integrated regulation, and intrinsic motivation (Malett et al., 2007). More broadly, they were given a mean score in each of the three categories of amotivation, extrinsic motivation, or intrinsic motivation. The SMS-6 is a 24-statement survey that is answered using a 7-point Likert scale in which participants must rate how much the statement corresponds with their reasoning for engaging in their sport (Pelletier et. al, 2001). There are 4 questions each that correspond to amotivation and intrinsic motivation, and 16 questions corresponding to extrinsic motivation.

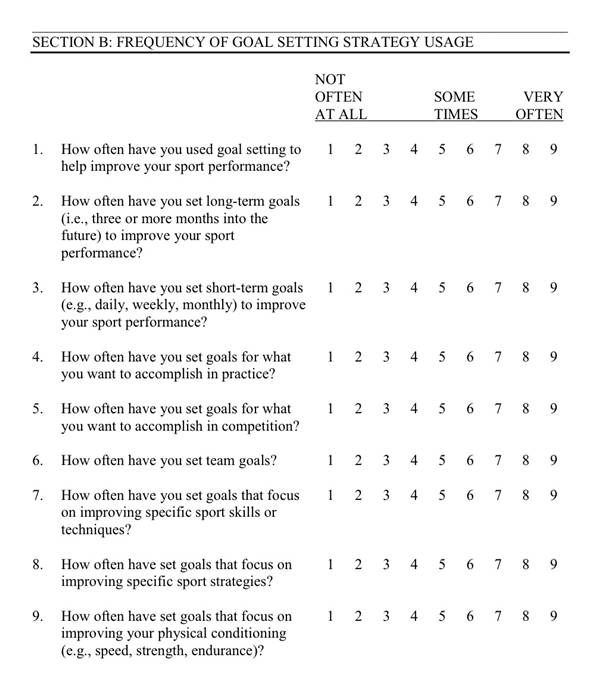

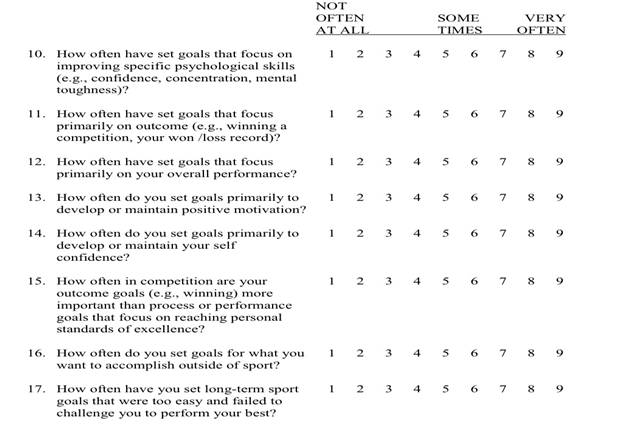

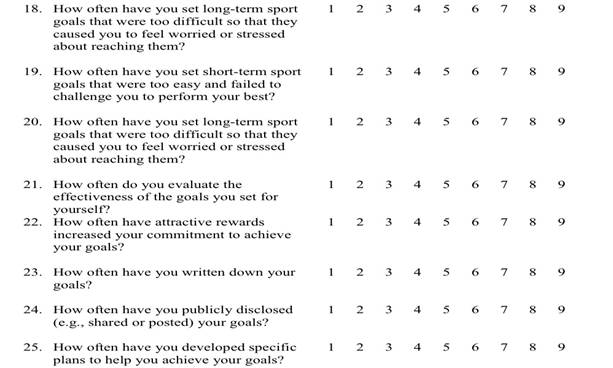

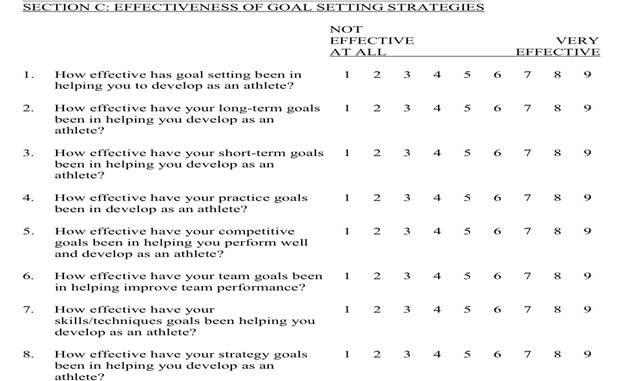

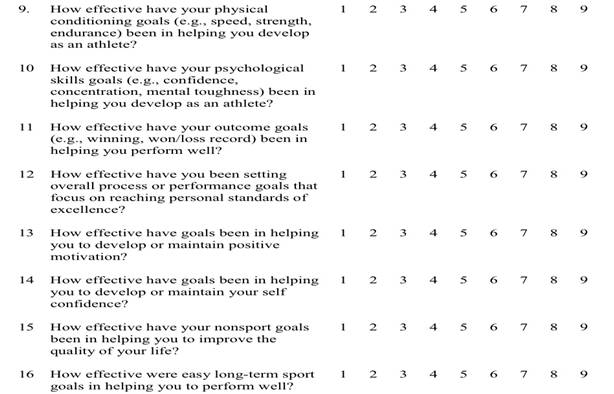

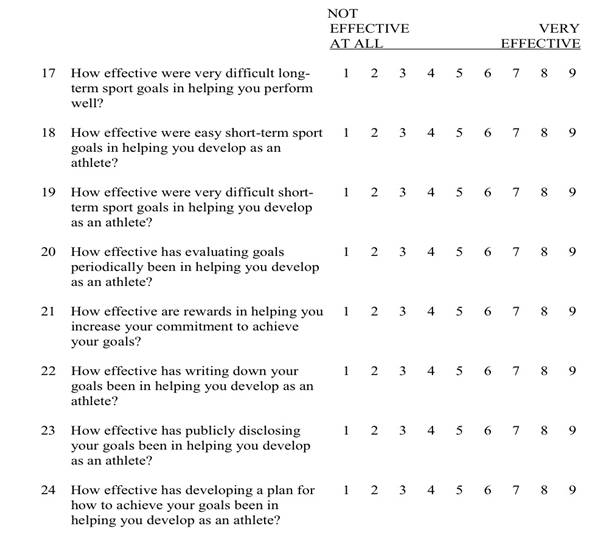

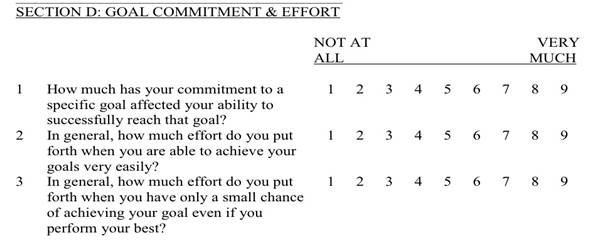

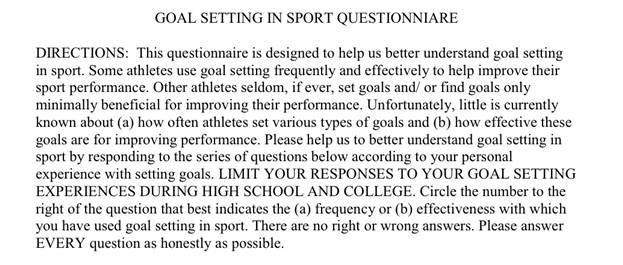

Additionally, the goal setting behavior was the dependent variable, measured by the Goal Setting in Sport Questionnaire (GSISQ, Appendix B). Three variables within goal-setting behavior were explored: goal setting frequency, goal setting effectiveness, and goal commitment and effort (Weinberg et al., 1993). The GSISQ has four sections; the first asks for background information including age, gender, years of experience in sport, and self-perceived athletic ability. The next section contains 25 questions about the frequency of goal-setting, answered on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from "not often at all" to "very often." The third section questions effectiveness of goal-setting and consists of 24 questions answered on another 9-point Likert scale ranging from "not effective at all" to "very effective." The last section pertains to goal commitment and effort and contains 3 questions that are answered on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from "not at all" to "very much." The questionnaire also has a fifth section concerning goal-setting preferences, but this section was omitted.

In order to collect data for this study, all subjects were asked to participate in person. Participation was completely voluntary, and data were anonymous after the athlete filled out the questionnaires. The coach of the D1 basketball team was asked for permission to administer the questionnaires after a team practice, and he allowed questionnaires to be handed out after practice was over. No compensation was provided to these athletes, as it is against university and NCAA policy. Recreational athletes from the Flynn Recreational Complex at the basketball courts were also recruited. Athletes who had not yet begun playing or had just finished playing basketball were asked to participate on site. All participants were required to sign an informed consent form and were informed of the purpose of the study as well as their rights as a participant.

All of the data were entered into SPSS, using a different column to enter the responses of each and every question on both questionnaires. Then, by adding the appropriate columns, new variables were created that provided mean scores for each participant in the categories of a) amotivation, b) extrinsic motivation, c) intrinsic motivation, d) goal frequency, e) goal effectiveness, and f) goal commitment and effort. A higher score in each category corresponded to either more of that motivation type or more of that particular goal-setting practice. Descriptive statistics were completed for general information. Pearson correlations were used to determine whether there was any correlation between any of the six factors being considered. Correlations were considered within motivational types, within goal setting behaviors, and between these two factors. A one-way ANOVA was also conducted to detect any difference between the two samples being tested. After some findings proved to be significant, three regression analyses were performed on the data.

Results

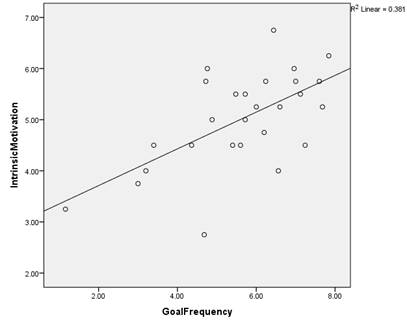

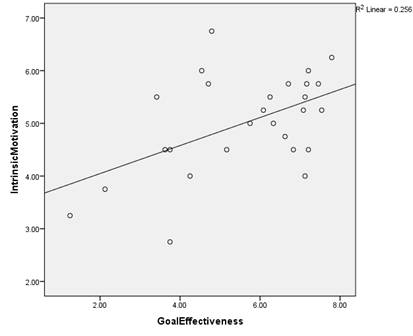

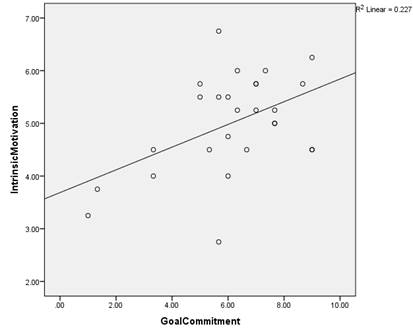

Descriptive statistics describe the data set for all variables. Table 1 displays the extent to which participants characterized themselves as amotivated (M=2.31, SD=1.57), extrinsically motivated (M=3.99, SD=0.99), and intrinsically motivated (M=5.01, SD=0.94). Furthermore, participants were similarly scored on the frequency with which they set goals (M=5.61, SD=1.61), how effective they believe their goals to be (M=5.62, SD=1.78), and their commitment to their goals (M=6.14, SD=2.07), which are displayed in Table 2. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed in order to assess the relationships between the three types of motivation. A moderate correlation between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation was observed, r(25)=.409, p<0.05. Pearson correlation coefficients were also computed for the relationships between each of the three factors of goal setting behavior. There was a very strong correlation between goal frequency and goal effectiveness, r(25)=.891, p<0.01, between goal frequency and goal commitment, r(25)=.804, p<0.01, and between goal effectiveness and goal commitment, r(25)=.849, p<0.01. Moreover, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to determine whether any significant relationship existed between motivational type and any of the goal setting behaviors. Table 3 presents the data showing significant correlations between intrinsic motivation and goal frequency, r(25)=.617, p<0.05, intrinsic motivation and goal effectiveness, r(25)=.506, p<0.05, and intrinsic motivation and goal commitment, r(25)=.476, p<0.05. Graphical representations of these correlations in Figures 1, 2, and 3, more clearly depict the correlation between intrinsic motivation and goal frequency, goal effectiveness, and goal commitment, respectively. Additionally, a one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the effect of motivation type and goal setting behavior between recreational athletes and D1 athletes. The results are seen in Table 4; there was no significant effect of either motivational type or goal setting behavior at the p<0.05 level for the two sample groups.

Table 1

Types of Motivation ReportedN Minimum Maximum Mean Std. Deviation Amotivation 27 1.00 5.75 2.31 1.57 ExtrinsicMotivation 27 2.19 6.13 3.99 0.95 IntrinsicMotivation 27 2.75 6.75 5.01 0.94

Table 2

Goal Setting Behavior ReportedN Minimum Maximum Mean Std. Deviation GoalFrequency 27 1.16 7.84 5.61 1.61 GoalEffectiveness 27 1.25 7.79 5.62 1.78 GoalCommitment 27 1.00 9.00 6.14 2.07

Table 3

Correlations between Motivation Type and Goal Setting BehaviorAmotivation Extrinsic

MotivationIntrinsic

MotivationGoal

CommitmentGoal

FrequencyGoal

EffectivenessAmotivation Pearson Correlation 1 .338 .287 -.249 .042 -.154 Sig. (2-tailed) .085 .147 .210 .834 .444 N 27 27 27 27 27 27 ExtrinsicMotivation Pearson Correlation .338 1 .409* .138 .326 .153 Sig. (2-tailed) .085 .034 .492 .097 .447 N 27 27 27 27 27 27 IntrinsicMotivation Pearson Correlation .287 .409* 1 .476* .617** .506** Sig. (2-tailed) .147 .034 .012 .001 .007 N 27 27 27 27 27 27 GoalCommitment Pearson Correlation -.249 .138 .476* 1 .804** .849** Sig. (2-tailed) .210 .492 .012 .000 .000 N 27 27 27 27 27 27 GoalFrequency Pearson Correlation .042 .326 .617** .804** 1 .891** Sig. (2-tailed) .834 .097 .001 .000 .000 N 27 27 27 27 27 27 GoalEffectiveness Pearson Correlation -.154 .153 .506** .849** .891** 1 Sig. (2-tailed) .444 .447 .007 .000 .000 N 27 27 27 27 27 27 *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).Figure 1

Correlation Between Intrinsic Motivation and Goal Frequency

Figure 2

Correlation Between Intrinsic Motivation and Goal Effectiveness

Figure 3

Correlation Between Intrinsic Motivation and Goal Commitment and Effort

Table 4

One-way ANOVA Between Recreational Athletes and DI Athletes

Sum of Squares df Mean Square F Sig. Amotivation Between Groups .064 1 .064 .025 .876 Within Groups 64.260 25 2.570 Total 64.324 26 ExtrinsicMotivation Between Groups .091 1 .091 .098 .757 Within Groups 23.233 25 .929 Total 23.324 26 IntrinsicMotivation Between Groups 1.944 1 1.944 2.330 .139 Within Groups 20.866 25 .835 Total 22.810 26 GoalFrequency Between Groups 6.255 1 6.255 2.564 .122 Within Groups 60.990 25 2.440 Total 67.245 26 GoalEffectiveness Between Groups 8.215 1 8.215 2.761 .109 Within Groups 74.389 25 2.976 Total 82.604 26 GoalCommitment Between Groups 15.130 1 15.130 3.938 .058 Within Groups 96.039 25 3.842 Total 111.169 26 In order to determine the percentage of variance in goal setting behavior explained by motivational factors, three different regression analyses were performed. All of the motivation types explained a significant proportion of variance in goal setting frequency, R2=.415, p<0.05, while intrinsic motivation alone explained a large portion of that variance, R2=.304, p<0.05. Table 5 shows that intrinsic motivation significantly predicts goal setting frequency, b=.613, t(23)=3.46, p<0.05. Similar results were found for both goal setting effectiveness and goal commitment and effort. All of the motivation types explained a significant proportion of variance in goal setting effectivness, R2=.354, p<0.05, while intrinsic motivation alone explained a large portion of that variance, R2=.283, p<0.05. Table 6 shows that intrinsic motivation significantly predicts goal setting effectivness, b=.592, t(23)=3.17, p<0.05. In both of these cases, neither amotivation nor extrinsic motivation contributed uniquely to the goal setting practices. Likewise, all of the motivation types explained a significant proportion of variance in goal comittment, R2=.390, p<0.05, while intrinsic motivation alone explained a large portion of that variance, R2=.271, p<0.05. Table 7 shows that intrinsic motivation significantly predicts goal setting comittment, b=.581, t(23)=3.21, p<0.05. Amotivation also had a significant unique contribution to goal commitment, predicting a lack of goal commitment and effort, b=-.431, t(23)=-2.46, p<0.05.

Table 5

Significant Effect of Intrinsic Motivation on Goal FrequencyModel Standardized Coefficients t Sig. Beta 1 (Constant) 9.699 .000 Amotivation .042 .212 .834 2 (Constant) 2.541 .018 Amotivation -.076 -.374 .712 ExtrinsicMotivation .352 1.720 .098 3 (Constant) -.104 .918 Amotivation -.179 -1.042 .308 ExtrinsicMotivation .136 .753 .459 IntrinsicMotivation .613 3.455 .002 a. Dependent Variable: GoalFrequency

Table 6

Significant Effect of Intrinsic Motivation on Goal EffectivenessModel Standardized Coefficients t Sig. Beta 1 (Constant) 9.663 .000 Amotivation -.154 -.778 .444 2 (Constant) 2.953 .007 Amotivation -.232 -1.109 .279 ExtrinsicMotivation .231 1.105 .280 3 (Constant) .381 .707 Amotivation -.331 -1.831 .080 ExtrinsicMotivation .023 .120 .905 IntrinsicMotivation .592 3.174 .004 a. Dependent Variable: GoalEffectiveness

Table 7

Significant Effect of Intrinsic Motivation on Goal CommittmentModel Standardized Coefficients t Sig. Beta 1 (Constant) 9.731 .000 Amotivation -.249 -1.286 .210 2 (Constant) 2.889 .008 Amotivation -.334 -1.639 .114 ExtrinsicMotivation .251 1.231 .230 3 (Constant) .312 .758 Amotivation -.431 -2.456 .022 ExtrinsicMotivation .047 .253 .803 IntrinsicMotivation .581 3.206 .004 a. Dependent Variable: GoalCommitment Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to explore goal-setting practices (i.e. goal frequency, goal effectiveness, and goal commitment) with regard to the three types of motivation exhibited by individuals in the context of sports. The secondary purpose was to determine whether a difference existed in goal-setting behavior and motivation types between recreational athletes and D1 athletes. This study hoped to determine whether motivational type could be used to predict a person's goal-setting behaviors.

Generally, participants displayed a correlation between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, suggesting that when one type of motivation was present, so was the other. This is a logical finding, considering that when a person is motivated, it is very rare for them to be completely motivated by intrinsic factors or completely motivated by extrinsic factors. A person either tends to be amotivated, or more often, they are motivated to a certain extent by a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Moreover, extremely strong correlations between the three facets of goal-setting behaviors present an intuitive finding that all of these factors are very closely related. It is possible that people who set goals more frequently only do so because they are effective, and those who do not find goals effective do not set them as often. Thus, both of these factors are highly correlated. Likewise, in order for a goal to be effective, a person must commit to it, accounting for the correlation of the third factor.

More interestingly, the correlation between intrinsic motivation and higher scores on all of the goal-setting behaviors indicate that those who are intrinsically motivated are more likely to set goals that are effective. The results of the regression analyses demonstrate that motivational factors account for the variance in goal setting behaviors, but that above and beyond the role of amotivation and extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation plays a significant role in predicting goal-setting behaviors. Thus, my original hypothesis that intrinsically motivated athletes use goal-setting more often and find it to be more effective holds true. These athletes are concerned with engaging in the sport of basketball for the sport itself and thus want to improve their performance for internal reasons. They evidently set and commit to goals because they find goals to be effective in enhancing performance. It is also noteworthy that extrinsic motivation plays no predictive role in goal-setting behavior, implying that if a person is motivated by external outcomes, they will not employ goal-setting techniques at a significant level. Additionally, the finding that amotivated individuals exhibited less commitment and effort to their goals validates this portion of the questionnaire; a lack of effort is a characteristic of amotivated individuals.

Nonetheless, my second hypothesis was not supported by the results of this study. The participants did not differ on their motivational type or the extent to which they set goals depending upon whether they were recreational athletes or D1 athletes. It is interesting that athletes who are expected to keep up a certain high standard of play and ability do not employ goal-setting more often than those who simply play basketball for recreational purposes. However, this returns to the idea that these athletes are not primarily influenced by what is expected of them, but rather by what they expect of themselves. The results of this study imply that if a person proves to be intrinsically motivated, which most are to some extent, then employing goal-setting techniques may help to improve their performance. The more athletes reported using goal-setting, the more effective they deemed goal-setting to be, indicating that it aids in improving performance. Thus, it can be interpreted that the internal drive to succeed is one of the factors that helps athletes persevere when pursuing challenging goals.

Limitations to this study were most prominently the sample size and accuracy of self-report. There were only a small number of athletes who completed the questionnaire, and they all only played basketball. Thus, these findings are not widely applicable to many other populations, as they cannot be applied to athletes who play other sports. All athletes completed this rather long questionnaire at a time when most would rather be playing basketball. This could have led to the athletes answering questions in a hurry and not reading questions carefully. Thus, it would help to shorten the questionnaire for future studies to ensure that athletes are not simply answering as quickly as possible to finish sooner. However, to some extent, this variability can never be controlled if the participants are answering the questions on their own.

Future studies should focus on whether these interactions between motivational type and goal-setting would alter if the researcher set the goals for the participant. Although this would only test short-term goals, it would be interesting to determine whether intrinsically motivated individuals were better able to achieve goals that a researcher set for them while completing a certain task. Because these athletes are internally driven, such a study would determine if they are equally as driven to achieve someone else's expectations as they are when achieving their own. This type of study could contribute to the knowledgebase for coaches and coaching techniques that could be used with athletes of different motivational types.

Overall, intrinsic motivation has proven to be a strong predictor that an athlete will set goals often while participating in his or her sport. These intrinsically motivated athletes are also more likely to commit to these goals and find them to be more effective in improving their performance. According to the present study, intrinsic motivation is the only type of motivation that can predict that an athlete will set goals, implying that these athletes are interested in employing this method to improve their own performance. The results of the present study allow us to better appreciate the differences present among athletes so we can recognize that tailoring every athlete's training regimen can optimize performance and improvement.

References

Bar-Eli, M., Tenenbaum, G., Pie, J. S., Btesh, Y., & Almog, A. (1997). Effect of goal difficulty, goal specificity and duration of practice time intervals on muscular endurance performance. Journal of Sports Sciences, 15, 125-135.

Briere, N. M., Vallerand, R. J., Blais, M. R., & Pelletier, L. G. (1995). De` velopment et validation d'une mesure de motivation Intrinse` que, Extrinse` que et d'amotivation en contexte sportif: L'Echelle de Motivation dans les Sports (EMS)/Development and validation of a scale on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and lack of motivation in sports: The scale on motivation in sports. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 26, 465–489.

Brookfield, D., & Wilson, K. (2009). Effect of goal setting on motivation and adherence in a six-week exercise program. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7, 89.

Burton, D., Gillham, A., Weinberg, R., Yukelson, D., & Weigand, D. (2013). Goal setting styles: examining the role of personality factors on the goal practices of prospective olympic athletes. Journal of Sport Behavior, 23, 23.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum.

Isoard-Gautheur, S., Guillet-Descas, E., & Duda, J. L. (2013). How to achieve in elite training centers without burning out? An achievement goal theory perspective. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14, 72-83.

Kane, T. D., Baltes, T. R., & Moss, M. C. (2001). Causes and consequences of free-set goals: An investigation of athletic self-regulation. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 23, 55-75.

Kleingeld, A., Mierlo, H. v., & Arends, L. (2011). The effect of goal setting on group performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 1289-1304.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1985). The application of goal setting to sports. Journal of Sports Psychology, 7, 205-222.

Pelletier, L. G., Fortier, M. S., Vallerand, R. J., Tuson, K. M., Brie` re, N. M., & Blais, M. R. (1995). Toward a new measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation in sports: The sport motivation scale (SMS). Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17, 35–53.

Pelletier, L. G., Fortier, M. S., Vallerand, R. J., & Brie` re, N. M. (2001). Perceived autonomy support, motivation, and persistence in physical activity: A longitudinal investigation. Motivation and Emotion, 25, 279–306.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54-67.

Ryska, T. A. (1998). Cognitive-behavioral strategies and precompetitive anxiety among recreational athletes. Psychological Record, 48, 697-708.

Weinberg, R., Bruya, L., & Jackson, A. (1985). The effects of goal proximity and goal specificity on endurance performance. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7, 296-305.

Weinberg, R. S., Burton, D., Yukulson, D., & Weigand, D. (1993). Goal setting in competitive sport: An exploratory investigation of practices of collegiate athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 7, 275-289.

Appendix A

Sport Motivation Scale-6

Appendix B

Goal Setting in Sport Questionnaire

Age _____________

Years of Experience in Current Sport _______________

Rate your athletic ability compared to the best athletes you regularly compete against:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A Lot Somewhat About Somewhat A lot

Lower lower the same higher higher

|