|

Kappa Omicron Nu

FORUM

Enriching Home Economics Philosophy with Phenomenological Insights:

Aesthetic Experiences, Bodily Being, and Enfolded Everyday Life

Henna Heinilä

HAAGA-HELIA University of Applied Sciences School of Vocational Teacher Education

2014

Prologue

This article is a statement about the importance and meaning of subjective experience in the context of the philosophy of home economics. What is subjective experience? Persons experience phenomenon differently, and their interpretation of that experience, the meaning it has for them, is hard to put into words. As well, these subjective experiences, like listening to music, reading a book, even family life, cannot be objectively measured by others (Cycleback, 2005).

The focus of the article is on matters that lay beyond the practical and visible surface of daily life—that is, on experiences, on subjective viewpoints, and on the ontological roots of the phenomenon called "everyday life." Examining things like being, becoming, existence, and reality (i.e., people's ontological roots) is a way for people to interpret the meanings they assign to their lives on a daily basis. Meaning interpretation enables meanings to be heard and seen, an important aspect of wellbeing and managing one's life.

To address this subjective dynamic of everyday life, this article mixes up different genres of writing. Besides the traditional scientific writing, the fingerprint of prosaic and drama will be identified. The metaphoric style is also strong. Mixing up different styles is allowed because the inquiry is phenomenological (i.e., involving the study of the structure of experiences). Phenomenology invites many ways of knowing and many ways of writing, too (Heinilä, 2007, 2012; Henriksson & Friesen, 2012; Vaines, 1998, 2004). In particular, this article uses family life in Nordic-European culture as a working example of phenomenological reflection.

Introduction

The essential assumption of this article is that meaning interpretation promotes wellbeing. This assumption leads to taking account of "small occasions" of daily living, like driving a child to ice hockey practice or planting a flower plant in the garden. Small occasions are a source for further argumentation or meaning making in daily life. A metaphor serves to illustrate this idea. Small occasions are like logs in a river, and argumentation is like timber rafting. The whole lived experience is intertwined in a single small occasion. It is like a sample of lived experience with a story in it—for example, a log holds the story of a tree. The river flow is akin to philosophical thinking, striving for ideas like the raft of logs and phenomenological reflection like whirlpools.

The premise of this article is that small occasions can be interpreted through the ideas of phenomenological theory (focused on the structure of people's experiences) with the intention of embedding them in the bigger story of life or being-in-the-world—like a raft includes the story of a forest. These previous metaphoric lines aim to clarify the importance of meanings experienced in the course of everyday life. The lines help make the point that there is a need for further philosophical inquiry in the field of home economics science. This article strives to reveal what kind of knowledge a phenomenological study can promote and what kind of body of knowledge it constructs for home economics professionals.

The everyday life considered in this article is focused on the life-world, instead of on individuals and families living that life. McGregor (2008) argued that this notion is typical for the Scandinavian or European home economics research paradigm. van Manen (2007, p. 6) explained how, in phenomenology, the researcher is keen on persons instead of individuals. The concept, individual, can be seen primarily as a biological term to classify a man or a woman involved in one's study. The concept, person, refers to the uniqueness of each human being. I agree with McGregor that Scandinavian home economists prefer the life-world-perspective in their studies, and I agree with van Manen that, in phenomenological research, this perspective points especially to persons instead of individuals. This kind of philosophical stance is adopted, explicitly at least, in several Finnish home economics studies (among others Haverinen, 1996; Heinilä, 2007; Janhonen-Abruquah, 2010; Korvela, 2003; Tuomi-Gröhn, 2008), although different theories, knowledge paradigms, and methodologies are used in them.

This article is based on my study Domestic heartbeat – Conversations with adult students on the course of their study (Heinilä, 2013), which is a typical example of a life-world-orientated phenomenological inquiry. The focus was on persons and their lived experiences. It represents a phenomenological insight into the daily life of adult persons. Finlay (2012, p. 19) argued that

. . . phenomenological research is phenomenological when it involves both rich description of lived experience, and where the researcher has adopted a special, open phenomenological attitude, which, at least initially, refrains from importing external frameworks and sets aside judgements about the realness of the phenomenon.

According to van Manen (2002), phenomenological inquiry represents an attitude of sensitivity and openness; it is a matter of openness to everyday, experienced meanings as opposed to theoretical ones. The theoretical framework and methodological procedure of my study were strictly based on these essential arguments (Heinilä, 2013). As well, this phenomenological framework affects the structure of this particular article, which reminds one of a spiral in the hermeneutic (interpretation) sense. Instead of being linear, from introduction to the conclusion, the structure of the article pursues a dynamic interplay among hermeneutic phenomenological research activities (in other words, the interpretation of subjective experiences and what they mean to people).

This approach to organizing the paper means that the "voice of the researcher" and "the voice of students" alternate. After the general presentation about methods (phenomenological attitude) comes theoretical findings, followed with descriptions (examples) of lived experiences. After that, again, the gaze is turned back to the interpretation, and more profound discussions about findings are shared. In the end, some thoughts are shared about how the body of knowledge of home economics philosophy is enriched with phenomenological insights. The headings in this paper are metaphoric, which is different from the acknowledged, traditional scientific procedure, but which reflect the phenomenological way of writing.

Making Waves – Discussing Daily Life with Adult Students

This section teases out the phenomenological attitude. During the course of everyday life, a lot of things happen, and our interest is usually keen on how we maintain and redo our practical daily duties. The philosophical reasoning behind this is not our first thought, although we know that there is something more beneath the practical surface. Philosophical thinking can make waves, make the surface move and let the bases and rocks of the action and performing be revealed. With bases and rocks, I refer to the question, "Why does the action happen, and why do people act the way they do in certain situations?" Repetition, continuity, shelter, love, and trouble, for example, are all aspects that make the human being feel alive and link daily practice into the meaning. Considering how and why all this daily life happens is meaning interpretation, mentioned in the beginning of the article. Why and how are also central questions for home economics philosophy, and they should be clearly explored through scientific research and dialogue. Home economics philosophy clarifies the public role of the profession and what is vital; it writes the examined words for societal benefits and the importance of home economics practice (see Hultgren, 1989; McGregor, 2012b; Vaines, 1989).

I work as a principal lecturer at the University of Applied Sciences, School of Vocational Teacher Education, in Finland. My job is to assist and guide the professional growth of student-teachers during their study. The students combine study and work. They are full-time workers whilst studying to gain their professional qualification. During the years 2010–2011, I conducted a reflective journey with my students, a journey into the course of everyday life, into the sediment of their daily life, considering the question: "How do adult students experience daily life when they have to combine work, family, and study during one year, and what kinds of things and aspects are meaningful and maintain wellbeing?" This journey was performed according to the demands of phenomenological inquiry and became the basic element of this research (see Heinilä, 2013).

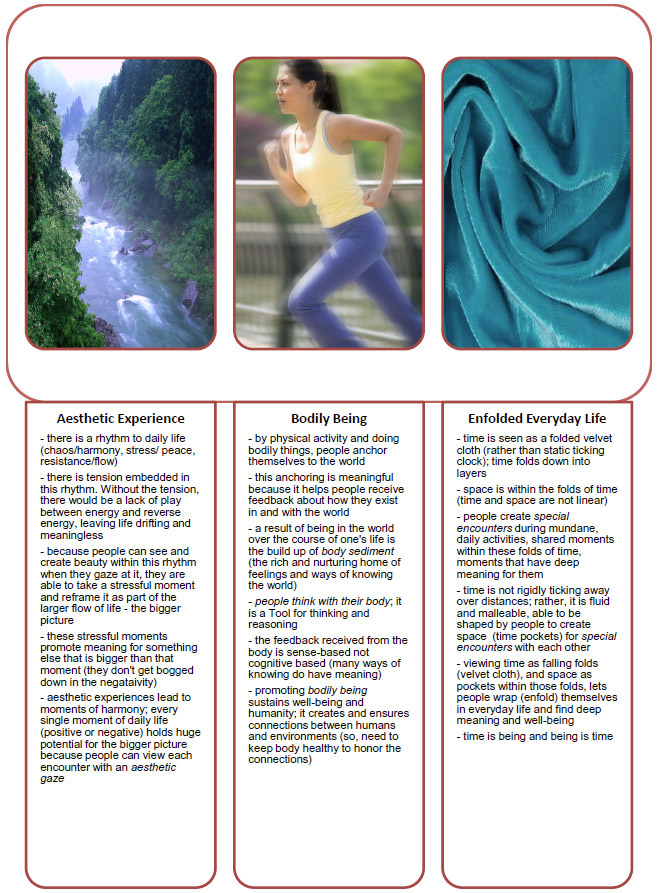

The study (Heinilä, 2013) revealed essential dimensions of the basic structure of everyday life. These dimensions turned out to be meaningful for the students. During the process of the study, these dimensions were modified as themes according to phenomenological interpretation. After that, the themes were named so that what was experienced as important factors in daily life could be discussed and commonly and professionally shared. Three meaningful themes were named: aesthetic experience, bodily being, and enfolded everyday life. I emphasize these three themes as special philosophical concepts of home economics (see Figure 1). The three themes describe the foundation, embedded in the human experience, upon which the whole phenomenon, daily life, is lived.

Figure 1

Three phenomenological concepts for home economics philosophy (figure prepared by Sue McGregor)

As mentioned, my phenomenological interpretation of adult learner students' lives revealed three important themes, which were strongly embedded in their daily experiences (Heinilä, 2013). After the meaningful dimensions were found and interpreted from the discussion with the students, it became apparent that the concrete talk about practice, actions, and relationships was incomplete. The need to discuss feelings, intuitions, wholes, and abstract notions, about something that could hardly be verbally described (that is, their subjective experiences), called for new means of expression. To that end, metaphors and various ways of writing entered the picture. There is no unambiguous explanation or model about how adult students experience the daily life and what kinds of things and aspects are meaningful for them. But, there are theoretical themes clarifying the context and picturing the ground from which adult students try to construct their daily lives in a meaningful way (see Figure 1).

The three themes—aesthetic experience, bodily being, and enfolded everyday life—are theoretical descriptions and philosophical arguments (see following text). They are part of the solid stratum of being-in-the-world, found when "digging and extracting the lived experience of adult students" in a suitable position and, to the right spot, within phenomenological method. The next section spirals into a discussion of how the same experience can be interpreted quite differently by different people. It strives to illustrate, for home economists, the interpretive power of phenomenological inquiry into everyday life. See McGregor (2012a) for a discussion of the concept of everyday life.

Making Visible – Illuminating Different Angles of an Experience

The following section sets out three descriptions considering one moment of a day from three different viewpoints: a hectic morning—moments of a two-child-family. The descriptions are short descriptions, like scenes, which are based upon the conversations recorded during the inquiry (Heinilä, 2013). These scenes are not quotations from my data; rather, they are mega-stories, which include essential aspects of experiencing such moments. Mega-stories show us not only what everyday stories could look like but what using them could feel like. These mega-stories were formulated and designed based upon the narrative nature of knowledge and narrative means of analyses of my research material. The idea of mega-stories also relies on the theory of interpretive inquiry (Bruner, 1987; Gadamer, 1975; Heikkinen, 2002; Hultgren, 1989).

Through these mega-stories, subjective and objective viewpoints are made visible. First, there is a subjective description, a mother living the morning moment of her family. Second, there is an objective description of a similar kind of moment, where the morning moment is looked at with an outsider's eyes. Finally, there is a professional's point of view of the morning moment—that is, my point of view, including my considerations as a home economics researcher and philosopher.

A morning moment from three different viewpoints

Scene one: subjective insight

Me having morning coffee in the kitchen

I love my life! It seems to be so familiar and nice. What could be more self-evident than the everyday course of my life with routine? I wake up in the morning, start to perform my daily life, and in the evening I feel satisfied. I encounter my family with pleasure, neighbors too. I am anxious to face my duties. If problems turn up, solutions usually follow. I have a strong notion of what my everyday life includes. I have this notion because of humankind. I realize that it is natural for the human being to observe his/her own being-in-the-world. It is not hard to consider the course of everyday life and recognize its importance for my wellbeing.

I am glad to notice that I love my husband, my children, my work, hobbies, and all kinds of family—and work-related components, including my daily life. Daily life, and especially at this very moment, a nice cup of coffee, although still a little bit too hot, keeps me happy, busy, and active. Soon, my husband will wake up the children . . . or he already did. The boys seem to be tired! They are hardly awake while my husband brushes their hair. I, involuntarily, leave my cup of coffee on the kitchen table, move toward the nursery, and start to pick up clothes for the children. For a moment, I only pick up different pairs of socks and unclean jumpers. But, as a handy mother, after a couple of minutes, I manage to dress the children. And soon, I am ready to leave home, after sipping cold coffee. I pick up the daily paper from the hall floor. I can hear my husband moaning in the study. I remember that he has an important meeting today. Goodbye, my Love, good luck, and have a nice day! With the children sitting in the stroller, I make my way to the kindergarten.

Scene two: objective insight

An outsider observing the morning moment of a mother, a father, and their children

There is a mother in the kitchen. She is, obviously, preparing morning coffee for herself and her husband. She looks calm and happy. The father is in the nursery, talking to his children, three- and five-year-old sons, trying to wake them up. The boys tend to continue sweet dreams, but the father carries them into the bathroom. Toothbrushes are waiting there in blue and green mugs. During the next fifteen minutes there is dressing, sweet talk, hard talk, crying, quarreling, too hot coffee, unread newspaper, too cold coffee, lost and found boot, and, finally, two well-dressed children sitting in the stroller, the mother pushing the stroller heading to the kindergarten, and the father sitting in a bus browsing through his day-schedule on his computer. The screen of the laptop reflects the father's eyes with tiredness, frustration, and a lot of worry.

Scene three: professional insight

A home economist sitting in front of her computer, preparing the study report

The science of home economics focuses on promoting human good and mastering family life. It also tends to create tools and procedures for professionals and families who are working for a better society. A home economist—sitting in front of her computer, researching family life, analyzing a two-child-family situation, and writing a research report—knows all this. But she also knows that the world is complex. What is good for one is not necessarily good for another. And what functions well in one circumstance functions badly in another context. She also knows that the global megatrends, individualization, economization, poverty, and climate challenges influence our capacity to perform as a family, at least as it is known in the traditional way. Human good has to be interpreted in the light of many different family circumstances, whimsical private and public economy, and unstable global environment situation. One idea promotes another, and the home economist continues her consideration.

The home economist will more often perceive single households, different kinds of partnerships, and living-apart-together-families than the traditional mother, father, and two-children-family model. Mothers and fathers are puzzled by the many demands they face. At the same time, when they feel they should create good circumstances for their children to grow and develop, they have to proceed in their career, earn money, develop themselves professionally, and, of course, serve the markets. Too often this is too much, confusing, and conflicting, and someone or something suffers.

The home economist has learned that the morning moment of a family, which she is now analyzing, is one view and example from the Scandinavian daily life. Scandinavian society lies, more or less, in the market economy and functions according to its laws. This means that mothers and fathers, like everybody else, must gain suitable education and professions, serve the markets and society, and earn a living for themselves and their families. To keep the economy vibrant and increasing, every citizen must be productive and consumptive. And if this is not enough, we are in trouble. Basic things like earning one's living, raising children, and taking care of the family are part of humanity and our culture, but economizing and monetary principles are shaking these basic conditions of living. Realistically thinking, the idea of strong family values stands apart, or even opposite, the market economy and individualization.

This idea makes the home economist stop. Her fingers arise from the keyboard. What can, and must, the home economist do? She cannot build her arguments only on a constantly changing and doubted practice. She knows that arguments on a shaky ground lack credibility and the capacity to grow and develop. But, what if there were some solid, theoretical tools and concepts that she could use to anchor her argumentation into the bigger whole? These theoretical tools and concepts, functioning as anchors, could present the philosophical body of knowledge of home economics science. Even if daily life is fragmenting, the home economist still must have ways to argue for human good and promote understanding. This is possible if the discipline's body of knowledge is philosophically based.

A philosophical body of knowledge needs to be rooted in practical perennial problems, values, and the essence of the human being. Yes, the home economist nods, philosophical argumentation is one option for her. It provides a solid foundation from which to develop practice. The home economist clarifies that the purpose of philosophical reflection is to grasp the essential meaning of everyday life and argue for its use by home economics professionals. When she puts down her fingers on the keyboard again, she decides to dig deeper—dig into the sediment of everyday life.

Feeling the Beauty in Daily Life – Seeing and Experiencing the Harmony

This section addresses the first theme: aesthetic experience. After I started the phenomenological interpretation of the conversations with the adult learner students (Heinilä, 2013), a surprise emerged. It became obvious that the students were not unhappy, stressed, tired, or frustrated, even though they were living, so-called, peak-years of family life. On the other hand, it would be wrong to acknowledge that they were not having those feelings, but it was not the point they found meaningful. Intriguingly, negative and stressful aspects of their life were found as a threat to wellbeing, but all these negative experiences were diminished by concentrating on positive experiences they had before and which they were assuming they would experience later.

A single stressful moment of a day was located in the context of the whole course of life–in the bigger picture. The stressful moment promoted meaning for something else, perhaps a-not-so-stressful moment. This interpretation revealed that under the stormy surface of daily life lies harmony. The human being is capable of creating and seeing beauty (the essence of this theme, aesthetic experience). It was amazing how students viewed themselves in large and harmonious wholes instead of staring at the hectic and difficult moments of a day or a week. They described how they preferred stress and chaos if it would promote harmony. In fact their aim was to experience the rhythm of stress and peace, chaos and harmony, and resistance and flow. The rhythm seemed to be the natural relationship between the human being and his/her environment. Without tension, embedded in the rhythm, there would be a lack of play between energy and reverse energy and the important pause, or stop, between these two different kinds of power. Without reciprocity and play intertwined in these energies, life became drifting and meaningless.

To further illustrate this theme, one student told a story about flower plants. She wanted to plant them in her garden. It was springtime and, as a teacher, she was busy at work and further study was just beginning. She wanted to plant flowers, no matter what. Flowers were for her like a framework: they would grow, blossom, and fade away. She felt that she could fasten her life course into the rhythm of flowers and nature. She wanted to add a concrete perspective into the rhythm. The rhythm allowed the structure, and the structure carried her on. Daily life became a place to meet beauty and harmony, like the entire life of a flower; daily life could be the natural place for aesthetic experience (Heinilä, 2013).

An aesthetic experience was chosen as the name for this theme, which emerged from and was interpreted during the phenomenological inquiry of my study (Heinilä, 2013). Dewey's (1934/2010) argument about art as an experience was a strong contribution to my interpretation. Dewey argued that the human being is willing to experience connection instead of disconnection. The aim is to promote and experience harmony. When the human being feels harmony, the aesthetic experience is revealed for him/her. Although Dewey's arguments refer to art, I consider his theory illuminating in the context of home economics theory and philosophy. Dewey pointed out that every single little experience in everyday life holds a huge artistic potentiality in itself. The idea of aesthetic experience in our daily life reveals in relationships between things and activities, parts and wholes, which will be encountered with an aesthetic gaze (see Mullins, 1986; Rehm, 1992).

Finding Oneself as a Bodily Being

The second theme is bodily being. This is a phenomenological term that captures the idea that a person's body is more than its interior; the body is also an external phenomenon that is in relationship to others. During the phenomenological interpretation process, I repeatedly noticed talk about running, walking, playing, eating, sleeping, feeling tired, feeling warm or cold, touching something, and other body-related actions (Heinilä, 2013). Quite often, students found these things wanted but not implemented. There was a strong yearning for fulfilling one's bodily functions. This notion was not surprising. There are plenty of theories about human being as a bodily being. Sociology and psychology, for example, approach the human being as a physical, psychic, and social and/or cultural creature. This kind of theoretical division seems natural, but it actually creates an artificial division, and it is not always beneficial from a practical point of view.

By way of explanation, philosophy is usually considered as a pure abstract approach into the world. But phenomenological philosophy has a different emphasis. Phenomenology wants to stay close to the phenomenon and find its nature and entity. Maurice Merleau-Ponty is a phenomenologist who has taken this emphasis seriously, especially regarding the human being's ontology. Merleau-Ponty (2002) argued that the human being is one whole, and the division into the body and mind cannot actually be made. Or, if it is divided, it will take the consideration away from actual being-in-the-world. According to him, the human being is in this world as a bodily being, including body and mind as a whole, and perceives the world primaryily through senses (because it is in relationship with others).

Intriguingly, intentionality is a body-based action instead of cognition-based. Intentionality is a philosophical concept referring to the mind's ability to form representations of things and has nothing to do with intentions. That intentionality is body-based (not mind-based) explains why, for example, exercise was so important to the students and why so many wanted to challenge themselves physically. Students anchored themselves, as is natural for the human being, to the environment and to the people with whom they were living, by doing exercise and physical work. The students felt this anchoring was meaningful; by acting physically and doing bodily things, they received feedback about how they existed in the world (remembering that phenomenology is life-world centered). The feedback they received from the world was sense-based, subjective and holistic, instead of cognitive-based, objective and non-holistic.

Because the ontology of the human being is essentially rooted in the bodily way of being (i.e., bodily being) (Merleau-Ponty, 2002), the structure of knowing must be considered as bodily-based, too. Knowing also includes intuitive and tacit knowledge, which is not verbal or external. People know things because they have experienced things. The body is like the ground with sediment, which is formulated during the life course: habits, skills, knowledge, techniques, and moral codes, for example. The body sediment is also the home of feelings. Feelings and many ways of knowing, together, let the human being experience his/her history (Heinilä, 2007; Parviainen, 1998).

The body is not only one extension among others for the human being. It seems to be an essential instrument for being a human being. The body is a Tool with a capital T, necessary for perceiving, and is therefore an essential Tool for action and reasoning. Shusterman (2006) argued that we do not only feel but think with our body. That is why we should exercise our body, get to know it, and try to become skillful with its uniqueness. Promoting bodily being sustains humanity, meanings, and connections between the human being and environments.

Facing the Solid Stratum – Something is Falling Down with Folds like Velvet Cloth

The final theme was named enfolded everyday life. One important thing for us as human beings is that we have the opportunity to become part of our social environment. There are many aspects—lack of time, tiredness, and lack of resources, for example—that disturb our social life. The theme, enfolded everyday life, relates to how we experience time and space and how we promote different encounters with others, even in the hectic course of daily activity. For example, a mother taking her eldest son to ice hockey practice several times a week makes this event a special occasion for her and her two younger children. Although the time and space refer to ice hockey practice and transportation from spot A (home) to spot B (ice stadium), there is another level altogether. There is the level of the mother's and other children's encounters, in the car and at the ice stadium, and the level of something special for them. The mother creates time for them to be together and to do the things of their own. Metaphorically speaking, the mother builds up "a fold" in a certain time and space for a special encounter to happen. Special encounter refers to a shared moment; mother and children do more than simply be together. This is one practical example of how daily routine can turn into meaningful experience when we use "mental levels" of time and space.

The metaphor of a fold also reflects a mental image of time, which is seen as falling down with folds like velvet cloth (so different from a stationary, ticking clock). The ontology of time, according to Heidegger (1996), includes an idea of layers. "What is, what was, and what is to become" exist and build the moment. At one space and time (one moment), we experience being-in-the-world multi-dimensionally. There are several possibilities to take mental or even physical positions. A moment offers us an opportunity to create special encounters between people in the middle of practical daily action. Because of this philosophical aspect, the metaphor grasps deeper than action description does. It tries to understand the notion that there is more in daily life than combining different activities. There is a mental level, lived experience, and emotions, all of which enable the meanings of practice to be revealed. And, although daily life sometimes could be boring, challenging, or hard to bear, meanings ascribed to the special encounter carry us on.

Because of the folded structure, this theme is named enfolded everyday life. Heidegger (1996) connected being-in-the-world ontologically to time and history; the core idea is that time is being and being is time. In his consideration, the line between temporal and non-temporal experiencing of time exists no more. Space and relationships also reflect time, not only the temporal measuring of it. The theme, enfolded everyday life, refers to the experience, which sets temporal and non-temporal time nested together. A mother and a child, in the student's story, encounter during the course of transportation activity. This occasion promotes meanings, wellbeing, and happiness in their lives.

Building up the Milestones – The Body of Knowledge of Home Economics Philosophy

This inquiry invited home economists to consider the phenomenon of everyday life as essential to home economics philosophy (see also McGregor, 2012a). In the beginning of the article, I claimed that the inquiry built the philosophical body of knowledge of home economics science. To clarify my claim, I now conclude with some remarks supporting this argument.

First, philosophical inquiry promotes ontological (reality), epistemological (knowing and knowledge), and axiological (values) dimensions of the phenomenon being found and discussed. Philosophy forms the implicit components of the discipline, and practice forms the explicit part of it (McGregor, 2012a,b; Vaines, 1997). Phenomenology allows me to suggest that the human being, as an experiencing and acting unit, is the entity of home economics, from both the discipline and professional points of view (different from the family as the basic unit).

Second, philosophical inquiry speaks out about what is fundamental for the home economics discipline and starts with it. In other words, in my inquiry (Heinilä, 2013), the lived experience of the adult students was asked, seen, and heard. The inquiry also asked, "How can the basic phenomenon of home economics be known?" With a phenomenological attitude and interpretation, the study attempted to stay as close to the day-to-day lives of adult students as possible. Lived experience was in focus and was examined within conversations and discussions. The source of knowledge existed in relationships and in dialogue, and was analyzed in it, not out of it. The knowledge created in the study aimed, eventually, to enhance adult students' sense of wellbeing. It also built a picture of home economics practice that connected subjective experiences to meanings in everyday life.

Third, the study (Heinilä, 2013) did not promote knowledge that would be directly usable in a mission-oriented profession—at least not in the practical sense. Practical insight helps to accumulate knowledge, or knowing, for the sake of doing something with it, in a practical context, for a better life (McGregor, 2012b). This study aimed, instead, to answer the question, "Why do people do certain things, and how do people make sense and meaning within their daily life—why home economics practice is and what it means?" The study delved into the core of a mission-oriented profession and studied the basic phenomenon in it (the human being). The knowledge created became one part of the philosophical body of knowledge of home economics (its sediment, to complete the metaphor) and created the meaning-perspective for home economics practice.

Finally, ontological, epistemological, and axiological dimensions of the philosophy of home economics can be seen as the milestones for scientific navigators. The word philosophy means

. . . the study [or love – philo] of wisdom, and by "wisdom" is meant not only prudence in our everyday affairs but also a perfect knowledge of all things that mankind is capable of knowing, both for the conduct of life and for the preservation of health and the discovery of all manner of skills. (Joll, ca. 2010, p. 2)

Conforming to this definition, the philosophy of home economics is the study of wisdom in the context of home economics. There are many ways to study this wisdom; all philosophical approaches are usable and available. They all increase the philosophical body of knowledge for home economics as discipline and practice, but my approach was phenomenological, and I found it extremely suitable for inquiring into the mystery of everyday life.

The application of phenomenology brought three special concepts to home economics philosophy: aesthetic experiences, bodily being, and enfolded everyday life (see Figure 1). Respectively, home economists can now view human beings as capable of viewing an array of daily experiences through an aesthetic gaze, positioning stressful moments in the greater scheme of things. They can assume that people think with their body by grounding themselves in each other and environments, thus meaning home economists must help people learn to sense the world through their connections with the world. Finally, home economists can propose that people are capable of creating special pockets of space within the folds of time, generating special encounters amongst the mundane daily activities—encounters that are meaningful and profoundly important for their well-being. A phenomenological philosophical lens helps home economists focus on everyday matters that are invisible and subjective but can be interpreted to discern their meaning of well-being.

On a final note, home economics provides practical insight into the society. It contains both individual and common aspects. The practical aspect is vital and is the main target for home economics researchers. But practice, and action in it, is not floating and drifting independently. The context always exists, like the history, intentions, and actors intertwined in it (see Badir, 1991; Turkki, 2012). Furthermore, the philosophical foundation of the discipline is more or less conscious for individual home economics professionals. I argue that because practice is anchored in human entity, the anchor can be made visible with philosophical argumentation. It is important for home economics researchers to know something of philosophical traditions. But, not everyone has to become professional philosophers in an academic sense (Brown, 1993; van Manen, 2007). They just have to remain open to the idea of philosophy, with one approach being phenomenology.

Epilogue

Scene four: subjective insight

Home again

I close the door behind me. The boys fall down on the hall floor giggling and squabbling together. They take off their outdoor clothes revealing their sweaty heads. Clothes remain on the floor when the boys hurry toward the nursery. I stand still, for a moment or two, but soon I find myself in the kitchen preparing dinner, something quick and easy. I hear my older son calling me, "Mother look, the puppy feels sick." I turn to him, and raise him and his toy-puppy in my arms. We have a short dialogue, meantime I continue preparing the dinner. Puppy needs our attention, and we shall give it within this short encounter in our kitchen.

I cannot deny that I feel exhausted right now. There are moments, like this, when I feel willing to leave all this. If I could just have a little time for myself, a tiny moment for my own thoughts and interests. But the door slams. My husband comes home, tired and tomorrow's duties on his mind. The boys have to climb up his legs, literally, until he pays a little attention to them. He carries the boys into the kitchen: one on his shoulders, one on the hip. It is time for dinner.

After a few hours, I sit next to my husband on the couch. We are planning next weekend. We decide not to go anywhere, not to do anything special. We are going to spend a day at home, relaxing, preparing good food, and perhaps watching a few funny movies with the children. That is the plan, and I feel that it will complete my doubts about the meaning of my life and turn my thoughts toward brighter sides of family life. Without stress and trouble, good and beautiful feelings would be empty, and vice versa. The tension these feelings generate keeps me moving and intending toward tomorrow.

References

Badir, D. (1991). Research: Exploring the parameters of home economics. Canadian Home Economics Journal, 41(2), 65-70.

Brown, M. M. (1993). Philosophical studies of home economics in the United States. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Bruner, J. (1987). Life as narrative. Social Research, 54(1), 11-32.

Dewey, J. (1934/2010). Taide kokemuksena. Antti Immonen & Jarkko S. Tuusvuori (Trans.). Tallinna: Eurooppalaisen filosofian seura ry/niin & näin. Orig. Art as Experience (1934).

Finlay, L. (2012). Debating phenomenological methods. In N. Friesen, C. Henriksson, & T. Saevi (Eds.), Hermeneutic phenomenology in education (pp. 17-37). Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Gadamer, H.-G. (1975). Truth and method. New York, NY: Seabury Press.

Haverinen, L. (1996). Arjen hallinta kotitalouden toiminnan tavoitteena. Kotitalouden toiminnan filosofista ja teoreettista tarkastelua. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopiston opettajankoulutuslaitos. Tutkimuksia 164. Academic dissertation.

Heidegger, M. (1996). Being and time. John Macquarrie & Edward Robinson (Trans.). Oxford, England: Blackwell. Orig. Sein und Zeit (1927).

Heikkinen, H. L. T. (2002). Whatever is narrative research? In R. Huttunen, H. L. T. Heikkinen, & L. Syrjälä (Eds.), Narrative research voices of teachers and philosophers (pp. 13-28). Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän Yliopistopaino.

Heinilä, H. (2007). Kotitaloustaidon ulottuvuuksia. Analyysi kotitaloustaidosta eksistentialistis-hermeneuttisen fenomenologian valossa (Doctoral dissertation, Kotitalous-ja käsityötieteiden laitoksen julkaisuja 16. Helsinki: Yliopistopaino). Retrieved from https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/20001

Heinilä, H. (2012). Writing new maps – Considering the phenomenological attitude as a theoretical framework for the future-orientated field of home economics. In D.

Pendergast, S. L. T. McGregor, & K. Turkki (Eds.), Creating home economics futures: The next 100 years (pp. 101-110). Queensland, Australia: Australian Academic Press.

Heinilä, H. (2013). Sydänääniä – keskustelua arjesta aikuisopiskelijan opintopolilla. (Domestic heartbeat – Conversations with adult students on the course of their study). Unpublished manuscript.

Henrikssin, C., & Friesen, N. (2012). Introduction. In N. Friesen, C. Henriksson, & T. Saevi (Eds.), Hermeneutic phenomenology in education (pp. 1-14). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Hultgren, F. (1989). Introduction to interpretive inquiry. In F. Hultgren & D. Coomer (Eds.), Alternative modes of inquiry on home economics research. Yearbook 9/1989 (pp. 37-59). Peoria, IL: Glencoe Publishing.

Janhonen-Abruquah, H. (2010). Immigrant women and transnational everyday life in Finland (Doctoral dissertation, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland). Retrieved from https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/20059/gonewith.pdf?sequence=2

Joll, N. [ca. 2010]. Contemporary metaphilosophy. In J. Fieser & B. Dowden (Eds.), The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from http://www.iep.utm.edu/con-meta/

Korvela, P. (2003). Yhdessä ja erikseen. Perheenjäsenten kotona olemisen ja tekemisen dynamiikka. Stakesin tutkimuksia 130. Helsinki: Stakes. Academic dissertation.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2008). Epilogue. In T. Tuomi-Gröhn (Ed.), Reinventing art of everyday making (pp. 271-278). Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2012a). Everyday life: A home economics concept. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 19(1), /archives/forum/19-1/mcgregor.html

McGregor, S. L. T. (2012b). The role of philosophy in home economics. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 19(1) /archives/forum/19-1/mcgregor2.html

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2002). Phenomenology of perception (C. Smith, Trans.). London, England: Routledge.

Mullins, C. G. (1986). Nurturing individuals and families. Journal of Home Economics, 78(3), 2-4.

Parviainen, J. (1998). Bodies moving and moved. Tampere, Finland: Tampere University Press. Academic dissertation.

Rehm, M. L. (1992). Art and aesthetics in home economics toward a practical problem approach. Journal of Vocational Home Economics Education, 10(2), 1-15.

Shusterman, R. (2006). Thinking through the body, educating for the humanities: A plea for somaesthetics. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 40(1), 1-21.

Tuomi-Gröhn, T. (Ed.) (2008). Reinventing art of everyday making. Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang.

Turkki, K. (2012). Home economics – A forum for global learning and responsible living. In D. Pendergast, S. L. T. McGregor, & K. Turkki (Eds.), Creating home economics futures: The next 100 years (pp. 38-51). Queensland, Australia: Australian Academic Press.

Vaines, E. (1989). On becoming a home economist: Conversations on the meaning. Home Economics Research Journal, 17(4), 319-329.

Vaines, E. (1997). Exploring reflective practice for HE. People and Practice: International Issues for Home Economists, 5(3), 1-13.

Vaines, E. (1998). A family perspective on everyday life: The heart of reflective practice. In K. Turkki (Ed.), New approaches to the study of everyday life – Part I (pp. 15-35). Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki.

Vaines, E. (2004). Postscript: Wholeness, transformative practices, and everyday life. In M. G. Smith, L. Peterat, & M. L. de Zwart (Eds.), Home economics now: Transformative practice, ecology and everyday life (pp. 133-136). Vancouver, BC: Pacific Educational Press.

van Manen, M. (2002). Writing in the dark. London, ON: The Althouse Press.

van Manen, M. (2007). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy (2nd ed.). Winnipeg, MB: The Althouse Press.

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Vija Dišlere,

Latvia University of Agriculture

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Aesthetic Experiences, Bodily Being, and Enfolded Everyday Life

Henna Heinilä

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Peng Chen PhD, Higher Vocational Education College, China Women's University

Peng Chen PhD, Higher Vocational Education College, China Women's University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Dr. Mary Gale Smith

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

|