Information Comprehension: Handwritten vs. Typed Notes

Karen S. Duran and Christina M. Frederick*

Sierra Nevada College

Keywords: Comprehension, Education, Handwritten, Note-taking, Recall, Technology, Typed

Abstract

Ever advancing trends in technology, and implemented in educational settings, inspired the current study, which examined the impact, on comprehension, of note-taking method. 72 undergraduate participants, aged 18-26, viewed a projected documentary in a classroom setting and took notes for a later assessment via either paper or computer keyboard. The Mann-Whitney U (Ryan & Joiner, 2001) showed a significant difference between the test scores produced via typed notes and written notes (p = .006). Experimental and survey results converge and dictate that the best and preferred practice for student note taking is writing.

Introduction

The move toward computers offers many advantages in education. Examples of these benefits are the ease with which students can obtain information and edit their academic papers for accuracy. Paper is used by both students and instructors for activities such as note taking, homework, and dispersal of information via handouts. The National Center of Educational Statistics stated, "100 percent of public schools have Internet access available in one or more instructional computers" (U.S. Department of Education, 2010, p. 313).

Today's technology both positively and negatively impacts the way people learn. Robinson-Staveley and Cooper (1990) stated that one positive aspect of using computers to type rather than handwrite essays is that the final product is viewed as superior by the reader. The typewritten format also allows for convenient proofreading, modification, and organization (Robinson-Staveley & Cooper, 1990). However, research evidence also indicates technology can negatively impact performance. For example, Cunningham and Stanovich (1990) conducted two experiments showing superior spelling performance for words learned via writing rather than typing. In the first experiment, Cunningham and Stanovich trained elementary aged children to spell words using a computer, letter tiles, or paper and pencil. Participants studied the words for four days by viewing 30 words written on 3 x 5 inch cards and reproducing words either by (a) using pencil to rewrite the word on paper, (b) using letter tiles to rewrite the word, or (c) using a computer keyboard to rewrite the word (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1990). A final spelling performance test took place after the study period and revealed a significant difference in spelling performance between groups with a benefit for participants in the written condition (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1990).

Cunningham and Stanovich (1990) replicated this study due to concern about the similarity between study (written) and test phases (written). In the replication, Cunningham and Stanovich verbally presented elementary age children with words during both study and test. During test, participants produced half of the words on a computer keyboard and half of the words using tiles (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1990). Results indicated that, regardless of test format (computer or tiles), the study phase format that most improved retention was writing (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1990). Generally, these two studies demonstrate word spelling is best retained when learning occurs via paper and pencil rather than computer keyboard or tile (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1990).

Longcamp, Boucard, Gilhodes, and Velay (2006) supported other studies in showing a learning benefit for characters studied via writing rather than typing and showed character orientation was another important factor relating to recognition. Participants learned 20 novel characters (letters from two unfamiliar alphabets displayed normally or mirrored) by viewing them on a computer screen and either writing or typing them during a study phase that lasted three weeks, one hour per week, and during which participants wrote or typed each character 20 times (Longcamp et al., 2006). Following the study phase, Longcamp et al. (2006) tested participant recognition for the, originally, unknown characters showing novel characters were better recognized when studied via writing versus typing. Longcamp et al. (2006) also address the importance of character orientation as this orientation is a consideration when children learn the alphabet (e.g., letters have a proper orientation) and argue written repetition assists visual character recognition as written movements support consolidation.

Longcamp, Boucard, Gilhodes, Anton, Roth, Nazarian and Velay (2008) conducted a study that produced results that coincided with Longcamp et al. (2006). Longcamp et al. (2008) tested recognition of initially novel, studied, characters in 12 right-handed participants (females and males) with no history of dyslexia. Participants studied 20 novel characters from unfamiliar alphabets for three weeks, once a week, for an hour each session (Longcamp et al., 2008). During study, participants were shown each character on a computer monitor and instructed to reproduce characters by either typing or writing them 20 times (Longcamp et al., 2008). Longcamp et al. (2008) tested participants on their ability to recognize the characters at four times after conclusion of the study phase, (a) immediately after the final study session, (b) after one week, (c) after three weeks, and (d) 5 weeks after the study period (Longcamp et al., 2008). Results showed study via handwritten repetition facilitates memory for longer than study via typed repetition (Longcamp et al., 2008). The results of this study indicate students may remember information contained in handwritten notes longer typewritten notes.

The topic of visual character recognition leads to another topic related to character representation: note taking. In education, note taking is important for student success. Igo, Riccomini, Bruning, and Pope (2006) had middle school students take notes by typing, writing, and copying and pasting relevant segments of the notes (Igo et al., 2006). Participants were asked to read a 763-word document about three native Australian minerals (Igo et al., 2006). The documents were either read in HTML format or on 8½ x 11 in. paper, depending on the randomly assigned condition (Igo et al., 2006). After taking notes, the children submitted their notes and took both a cued recall and multiple-choice test on the information (Igo et al., 2006). Igo et al. (2006) found written notes best facilitated cued-recall test performance and copying and pasting best facilitated performance on the multiple choice assessment.

Carter and Van Matre's (1975) conducted a study producing results that converge with findings of previous studies showing handwriting notes better facilitates recall due to opportunity for enhanced review. Carter & Van Matre (1975) instructed participants to listen to a lecture and assigned them to study by either (a) taking notes on paper and reviewing the notes, (b) taking notes on paper and mentally reviewing the notes, (c) carefully listening to the lecture and mentally reviewing the lecture, or (d) carefully listening to the lecture with no review but with a simple task provided to balance time. The test (immediate and delayed one-week) was accompanied by no time constraint and provided participants passages from the lecture with omitted words to be produced (Carter & Van Matre, 1975). Carter and Van Matre (1975) showed that note taking, coupled with subsequent review, was important for recall and also facilitated memory a week later.

Previous studies focused on participant processing or memory for novel characters and letters. The current study examined the impact of note-taking method (paper vs. laptop) on comprehension test performance. In the current study, participants were instructed to take notes, either on paper or via laptop computer, from a projected video documentary, and immediate comprehension was assessed using a recognition based, multiple choice test. Previous research (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1990; Igo et al., 2006; Longcamp et al., 2006; Longcamp et al., 2008) lead us to predict a difference in comprehension performance between those taking notes on paper and laptop computer, with a predicted benefit for the paper note-taking group.

Method

The current experiment was designed to examine the impact, on comprehension, of writing notes on paper or typing notes via laptop computer. The results of this study not only concern students, but also professionals in any setting who record information for later use.

Participants

Participants were 72 undergraduate students, aged 18-26, who received course credit for their participation. Participants were a convenience sample recruited via email and classroom announcements. On condition assignment, the 72 participants were equally distributed into one each of the two note-taking conditions (i.e., paper and laptop). Participants were assigned to note-taking conditions (i.e., paper vs. laptop) based on convenience related to the availability of a personal laptop.

Procedure

On arrival to the experimental session, participants were greeted and thanked for their time. Everyone was provided the informed consent document and given ample time to read and decide whether or not to participate. Participants were tested in classrooms pre-wired with a video projection system.

After deciding to participate, participants present in the room were polled for whether or not they had a personal laptop with them at the current time. Participants were not provided computers due to the role unfamiliarity with a new computer might have played in their ability to take accurate notes and concentrate on the documentary material presented to them. Those who reported they had a laptop were assigned to take notes via laptop computer and the remaining participants were assigned to the paper note-taking condition.

After note-taking conditions were assigned, participants were instructed to take notes on a 10-minute projected documentary on Angkor Wat (Stein, 2011). At this time, participants were informed they would take a comprehension test and general information survey at the conclusion of the documentary. Once the documentary was complete, participants in the paper note-taking condition turned their notes in and participants in the laptop note-taking condition were instructed to submit their notes to the researcher via email. This was done to provide evidence of participation and to facilitate categorization.

Once all notes were submitted, a 10-item, multiple choice, comprehension test (see Appendix B) was administered to all participants. No time restraint was imposed, however, participants were not permitted to use the notes they took during the documentary for the exam. At the conclusion of the comprehension test, participants completed a general information survey (see Appendix C) that included demographic (e.g., academic major) and note-taking related (e.g., preference) questions.

After the general information survey, participants were thanked for participating and any verbalized questions were addressed. The experiment lasted no more than 30 minutes and participants were tested once.

Materials

Participants were asked to use their own laptops to take notes on the documentary due to convenience, familiarity with the keyboard, and minimization of distraction. Not only would it be financially prohibitive to have several of the same model laptop computers on hand but participant familiarity with the laptop would be varied. This unpredictable variance could produce time management issues and the distraction of typographical errors produced due to familiarity with another keyboard. Use of personal laptop computers meant each participant had reasonable familiarity with keyboard layout while taking notes. Participants writing their notes were provided lined, college ruled, notebook paper.

Participants viewed a projected documentary video about Angkor Wat (Stein, 2011). This was the content on which participants were asked to take notes. After the documentary was complete, participants were asked to complete a comprehension test (see Appendix B) on the material from the documentary. Finally, participants completed the general information survey (see Appendix C), which posed demographic questions in addition to questions relating to their note-taking habits.

Results and Discussion

The ratio data from the comprehension test were sorted into groups according to note-taking mode. The non-parametric alternative to the two-sample t-test, the Mann-Whitney U (Ryan, & Joiner, 2001),was used to analyze the data. The Mann-Whitney U was used because the comprehension test data set was truncated, ranging from a minimum score of 1 to maximum score of 10.

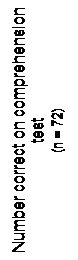

Figure 1 (see Appendix A) shows the number of correct answers on the comprehension test for each participant, sorted by condition. The scores indicate the number of correct responses of the possible 10. A significant difference was found between comprehension test scores for those in the paper note-taking condition and those in the laptop note-taking condition (U = 889.0; p = .006). Those in the paper note-taking condition scored better on the comprehension test than those in the laptop note-taking condition.

The preference for writing vs. typing notes was also analyzed. Participant responses to the 10-item general information survey (see Appendix C) were arranged from one to ten, and particular focus was placed on participant response to the fourth question that asked about personal preference regarding note-taking method. These responses were analyzed using the Chi-square test. A significant difference (p ≤ 0.001) indicated a preference for writing rather than typing notes.

Under the conditions of the current study, handwriting rather than typing notes better facilitates comprehension and is also the preferred note-taking mode. This finding is in line with Longcamp et al. (2006) who found writing vs. typing novel characters facilitated identification and Cunningham's and Stanovich's (1990) finding that writing, rather than typing or using tiles to produce words, lead to superior spelling performance. In a society where technology so quickly evolves, our results show writing remains integral to the educational process.

While note-taking mode is relevant, it is also important to recognize notes are maximally beneficial when reviewed. Carter and Van Matre's (1975) results indicate, when coupled with review, notes taken on paper are more beneficial to memory than listening and mentally reviewing content. An interesting future direction would be to consider the relative benefits of taking notes on paper or computer keyboard when accompanied by opportunity for review.

One limitation of the current study is that the amount of previous experience participants had typing notes on their computer was not assessed. A relevant consideration in future studies on this topic would be to survey duration of computer ownership, typical note-taking methods, and formal typing course experience. In the current study, the impact of this variable was minimized by allowing participants the same amount of time to write or type notes. Another potential limitation of the current study is this study addressed only shallow information processing. Future research could focus on deep processing induced by study, test method, or time between study and test.

The current study showed handwritten notes better facilitate comprehension, even on immediate test with no intervening study period. This information is beneficial as it, combined with the results of other studies, dictates a best practice for student note-taking. This finding is not relevant only to undergraduates but to anyone who takes notes on information to be used at a later time. This pattern may influence educators, school administrators, and information technology specialists to reevaluate the use of computers in classroom settings.

The benefits of written notes aside, the results of the current study and relation to others should not overshadow the role of computers as they do facilitate convenient information access and can be used as educational tools. Varying the tools used in any setting is a strength, and the classroom is no exception. Computers should not be the only tool used in a classroom, just as we have now diversified the classroom experience from paper. The challenge is to maximize the benefits (e.g., boredom reduction) and minimize the costs (e.g., potential distraction) of having computers in the classroom. Finding an ideal balance of existing and new technologies will allow instructors to serve their students in the best fashion.

References

Carter, J. F., & Van Matre, N. H. (1975). Note taking versus note having. Journal of Educational Psychology, 67(6), 900-904. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.67.6.900

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1990). Early spelling acquisition: Writing beats the computer. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 159-162. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.159

Igo, L., Riccomini, P. J., Bruning, R. H., & Pope, G. G. (2006). How should middle-school students with LD approach online note taking? A mixed-methods study. Learning Disability Quarterly, 29(2), 89-100.

Longcamp, M., Boucard, C., Gilhodes, L., Anton, L., Roth, M., Nazarian, B., & Velay, L. (2008). Learning through hand- or typewriting influences visual recognition of new graphic shapes: Behavioral and functional imaging evidence. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20(5), 802-815. doi:10.1162/jocn.2008.20504

Longcamp, M., Boucard, C., Gilhodes, J., & Velay, J. (2006). Remembering the orientation of newly learned characters depends on the associated writing knowledge: A comparison between handwriting and typing. Human Movement Science, 25(4-5), 646-656. doi:10.1016/j.humov.2006.07.007

Robinson-Staveley, K., & Cooper, J. (1990). The use of computers for writing: Effects on an English composition class. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 6(1), 41-48. doi:10.2190/N3WK-KC2Q-DVGD-7F0B

Ryan, B., & Joiner, L. B. (2001). Minitab handbook. Australia: Duxbury.

Stein, N. (2011, December 07). Digging for the Truth: Angkor Wat - Part 1 [YouTube]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OzR8lFXigko

U. S. Department of Education. (2011, December 05). Educational technology in U.S. public schools: Fall 2008 [Report]. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2010034

Appendix A

Note-taking ConditionFigure 1. The number of correct scores on the comprehension test, for each participant, are shown above and displayed by note taking mode (laptop computer or paper). The non-parametric alternative to the two-sample t-test, the Mann-Whitney U (Ryan & Joiner, 2001), was used to analyze the data. A significant difference was found between the test scores produced via typed notes vs. written notes (p = .006).

Appendix B

Comprehension Test

Please circle the letter that best answers the question.

- What does Angkor Wat translate into?

- City temple

- The lost city

- The complex temple

- The great city

- What civilization existed 800 years ago in Cambodia?

- Mongol empire

- Roman empire

- Mauya empire

- Khmer empire

- Where is Angkor located?

- Cambodia

- Italy

- Russia

- Africa

- How long did this civilization dominate Southeast Asia?

- 1100-1600 a.d.

- 800-1432 b.c.

- 800-1432 a.d.

- 300-1600 a.d.

- Angkor Wat is the world's largest ________________.

- Religious monument

- Lost city

- Oldest city

- Complex

- Why are the stairs so steep at Angkor Wat?

- They are easier to climb

- Steps are old and falling apart

- Represent the difficulty of getting into the kingdom of heaven

- People used to have small feet

- How tall is Angkor Wat?

- 213 ft

- 500 ft

- 3,000 ft

- 800 ft

- How many hells are there in Hindu mythology?

- 23

- 62

- 32

- 36

- How far do the carvings on the wall extend?

- 4 miles

- ½ mile

- 6 miles

- 1 mile

- What was Angkor Wat made of?

- Coolen mountain rocks

- Random rock

- Imported rock

- Granite

Appendix C

General Information Survey

Please circle or fill in the answer that best pertains to you.

- Are you currently enrolled in college?

- Yes

- No

- What subject do you find most interesting in college?

- Science

- Math

- Art

- Psychology

- Other: __________________

- Which device do you use more frequently?

- PC

- Mac

- I don't own a computer

- Other: __________________

- During a lecture, do you prefer writing your notes or typing them?

- I like both

- Depends on the subject

- I prefer typing

- I prefer writing

- Have you ever taken a typing class?

- No

- Yes

- I have excellent typing abilities.

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

- Is English your first language?

- Yes

- If no, what is? ___________

- How old are you in years? ____

- You are currently a…

- Freshmen

- Sophomore

- Junior

- Senior

- What is your major? __________

|