|

Kappa Omicron Nu

FORUM

BEYOND REPAYMENT: Microcredit Lending

A Viable Capacity-Building Strategy among Ghanaian Women

Gwendolyn M. Taylor

Career Planning Specialist

Ingham Intermediate School District, Mason, Michigan

Julia R. Miller

Department of Family and Child Ecology

Michigan State University, East Lansing

Introduction

This narrative shares the emerging work of a young initiative that

targets poor women in the developing country of Ghana, West Africa: the International Women’s MicroCredit Loan Development Program (IWMC).

This program is a service project of the Zonta Club of Lansing (Michigan).

Since 2005 IWMC has continued to support microlending as a viable economic

development strategy to promote the general welfare of women. Consistent with the mission of Zonta International—advancing the status of women worldwide—the Zonta Club of Lansing

engages in the international microcredit loan project to address persistent

poverty among women.

To this end, the Zonta Club of Lansing supports microcredit loan programs for two cohorts of women entrepreneurs in Ghana:

- A consortium of Rural Development Officers coordinates microcredit loans in three rural areas. This microcredit program is designed as a revolving loan model, potentially impacting 15-20 women per participating district

in each loan cycle. In these rural areas, lead community development officers facilitate entrepreneurship training and coordinate the lending program.

- An urban microcredit loan initiative provides an opportunity for the owner of a cottage industry/home based tailoring-seamstress business employing 15

employees to purchase an industrial sewing machine. The business incorporates a training component for participants to learn an advanced technical skill.

As past U.N. Secretary General, Kofi Annan of Ghana, stated in his

2005 proclamation introducing the International Year of Microcredit:

Sustainable access to microfinance helps alleviate poverty by generating income, creating jobs, allowing

children to go to school, enabling families to obtain health care, and empowering people to make the choices

that that best serve their needs. The stark reality is that most poor people in the world still lack access to

sustainable financial services, whether it is savings, credit, or insurance (U.N., 2005).

Ghana in Perspective

The Republic of Ghana is a nation of contrasts. Although rich in natural resources, including minerals, cocoa, rubber and a host of food products, Ghana is an exceptionally poor country. The average annual income is less than $400 U.S. (World Fact Book, 2007). The domestic economy revolves around subsistence agriculture, accounting for approximately 34 percent of the GDP and employing an estimated 60 percent of the workforce—mainly small landholders. By African standards, Ghana is not a very large country. It

ranks 30th in size of the continent’s 47 countries and has a land mass similar to the combined states of Illinois and Indiana (World Fact Book, 2007).

Juxtaposed to this exceptionally challenging economic backdrop, Ghana remains one of the more politically stable countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ghana was the first Sub-Saharan African country to gain independence from British colonial rule. In 2007, the nation celebrated 50 years of independence.

Although poverty in Ghana is pervasive, it is even more extreme in

most of the country's rural areas. According to the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), 70 percent of the country’s poor live in rural areas where they have limited access to basic social services, safe water, all-year roads, electricity, and telephone service (IFAD, 2007). Women are among the worst affected. More than half of

female heads of households in rural areas are among the poorest 20 percent of the

population. These women are the poorest of the poor. They disproportionately bear

workloads and are responsible for 55 to 60 percent of agricultural production. Women work at least twice as many hours as men, spend about three times as many hours transporting water and goods, and transport about four times as much in volume (IFAD, 2007). Yet, women are much less likely than men to receive education or health benefits, have access to credit, or have a voice in decisions affecting their lives. For these women, poverty means high numbers of infant deaths, undernourished families,

and a lack of education for children. Not unlike the majority of women across the African continent, economic contributions of Ghanaian women are inextricably linked to the very survival of the family as well as to the health and development of the nation.

Toward Appropriate Change

What appear to be intractable circumstances for millions of women are now confronted through often small, but intensely powerful efforts. The emerging work of the International Women’s MicroCredit Loan Development Program removes traditional barriers to loan acquisition, affording women an opportunity to begin or enhance a business. IWMC expands the opportunity for Ghanaian women to produce and market agricultural foodstuffs, craft products, or

services and sell products/services locally or distribute to broader markets. Embedding personal development strategies into program components promotes empowerment and leadership while encouraging women to become efficient and effective entrepreneurs.

In the broadest sense, microcredit is the principle of providing very small

loans to individuals, primarily the poor, having no access to the formal banking

system. Microloans offer the economically disenfranchised an opportunity to invest in self-employment projects, allowing them to care for themselves and their families. The essence of microbanking is

the replacement of traditional credit evaluation and lending practices with local community-based, lower-cost procedures.

The idea of making small loans to the very poor has perhaps been most popularized by economist Dr. Muhammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank and 2006 Noble Prize recipient for his pioneering work in microcredit lending (Grameen Communications, 2007). In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech Yunus offered:

The underlying premise of microlending is that the poor have skills. It is not their lack of skills, which make

poor

people poor. Rather, it is the institutions and policies that negatively impact poor people.... to eliminate

poverty all

we need to do is to make appropriate changes in the institutions and policies

and/or create new

ones. (Mjos,2006)

A Serendipitous Beginning

In 2002, a Ghanaian Hubert H. Humphrey Fellow, studying municipal government policies in the Lansing

area, was invited to a Zonta Club of Lansing meeting to address the impact of poverty on Ghanaian

women. She described the plight of local women and explained how a small amount of funding could significantly impact their lives. She

explained how $10 U.S. allowed a poor woman to purchase, feed, and fatten

a goat. Ultimately, sale of the goat for a profit would allow use of

part of the profit to purchase shoes so her daughter could attend school.

The speaker’s remarks inspired Club members to “pass the

hat.” In a matter of minutes Zonta members collected several hundred dollars to aid

women in Ghana. But equally important, the speaker's story fostered dialogue,

which became the catalyst for escalating the Club’s commitment to alleviating women’s poverty.

In 2003, a confluence of events offered an opportunity to significantly extend

that commitment. Coincidentally and completely unrelated to the

Club's growing commitment to support disenfranchised women in Ghana,

the authors

were engaged in several economic development projects in Ghana.

Taylor and Miller were able to leverage components of their ongoing economic development work to include the Zonta Club of Lansing as a partner

to target poverty reduction and alleviation. Additionally, the authors were able to facilitate travel to Ghana for several

Zonta Club of Lansing members. Travel to Ghana provided representatives an opportunity to deepen their

understanding and appreciation of the cultural and economic landscape impacting Ghanaian citizens, especially women.

Ghana's national poverty reduction structures focus on integration

of relevant aspects of culture and tradition into development plans. This intentional integration highlights growing

research that addresses the benefits of incorporating effective, appropriate cultural norms and traditions as part of

economic development improvement strategies (Smith & Thurman, 2007; Rhyme, 2001).

The authors used their established Ghanaian networks to bring together

significant stakeholder groups to collaborate on framing a pilot

microloan initiative. Stakeholders representing the target communities, university administrators and faculty,

the public and private sectors, and business interests worked with Club representatives to generate core-operating guidelines for the microloan program.

The following assumptions or operating principles guide the IWMC lending practice:

- Priority is on empowering women and building social capital through formation of groups.

- Loans are not charity.

- Loans are targeted to poor women.

- Loans are based on trust.

- Loans are not based on legal procedures, collateral, or legally enforceable contracts.

- Loans are offered for creating self-employment/income generating activities.

- Loans can be repaid in installments.

- Interest rates will not exceed the national market interest rate.

Stakeholders also formulated a set of working operating parameters:

- A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) will guide program implementation.

- The Zonta Club of Lansing will assume major responsibility

for fund raising to support the microlending project for years

01-03.

- 01-03 programming will be conducted as a pilot project.

- Assessment measures will be developed to identify

recommendations for improvement.

- A lead facilitator will be identified for each cohort.

- In year 01 the number of participating cohorts will not

exceed five.

- Program participants will be added based on the ability to appropriately

facilitate and monitor cohort programming.

- Citizen participation and capacity building will be integral components of the program.

- Decision making will be collaborative and data-driven.

- The project will complement Ghana’s national poverty reduction plan.

- The Club is committed to developing a programmatic infrastructure for building local capacity, which overtime assumes responsibility for sustaining and scaling-up the initiative.

IWMC was greatly advantaged by the leadership of the former Hubert H. Humphrey fellow who provided the impetus for the Club’s Ghana microcredit service project. As a Senior Rural Development Officer in the Ministry of Rural Development & Environment, she also served as lead facilitator for the IWMC rural consortium.

During their visit to Ghana, Lansing representatives also had a

chance to meet with local Zonta Club members. The Ghana Clubs arranged for Lansing representatives to visit the construction site of their

local service project targeting the eradication of violence against women.

Through their collaborative efforts, three Ghanaian Zonta Clubs raised funds and contributed sweat equity to erect the first women’s shelter in Ghana.

Around the world Zonta members are engaged in a myriad of service initiatives focusing on the economic security of women. Zonta International, a multicultural, multiethnic, multinational service organization, works to advance the status of women. Through its 1260 clubs in 67 countries, Zonta service initiatives are reframing constructs of economic security and sustainable development to include social, political, and economic conditions impacting human development, peace and security, and environmental conditions.

This reframing promotes a broader perspective of poverty. Specifically, this

view moves poverty from the absence of necessary goods and services (i.e., food, shelter, health care) to a broader perspective, one

encompassing both an absence of assets and opportunities (i.e., land for food production, access to trade markets) as well as an absence of skills and knowledge (i.e., basic education/skill training). This broader perspective of poverty represents

a core driver of IWMC.

The Persistence of Gender Inequality

Women confront formidable obstacles in obtaining equitable education, health care, employment, and fundamental freedoms—just because they are women. According to the United Nations Millennium Campaign to

reduce world poverty by 50 percent by 2015, the overwhelming majority of labor that sustains life—growing food, cooking, raising children, caring for the elderly, maintaining a house, hauling water—is done by women. Universally, this work is accorded low status and

most often no pay. This ceaseless cycle of labor rarely shows in an economic analysis of a society’s production and values.

Organizations that collect and aggregate information to document the relative consistency of the global positioning of women and girls (U.N. Millennium Campaign, World Bank, UNICEF, UNESCO, U.N. Population Fund,

& World Heath Organization) report the following findings:

- Globally, of the 1.3 billion people who lie in absolute poverty, 70 percent are women.

- Women work two-thirds of the world’s working hours.

- Women earn only 10 percent of the world’s income.

- Women own less than 1 percent of the world’s property.

- Women constitute two-thirds of the estimated world’s illiterate adult population, and girls make up 66 percent of the 77 million children not attending primary school.

- Around the world, an estimated 4 million women and girls are bought and sold each year.

- Each month, an estimated 40,000+ women in developing nations die from pregnancy related causes.

The feminization of poverty is overwhelming. Perennial gender inequality results in an “inequality trap”

that ends up reproducing other types of inequalities. The 2007 World Bank’s Global Monitoring

Report presents the vastness and complexity of factors impacting gender inequality and exacerbating the exclusion of major population sectors (World Bank, 2007). Evidence continues to grow

that when women are accorded gender equality through education and access to measures of economic sustainability, including credit, their participation results in higher contributions to a nation’s economic growth and poverty reduction. In great measure, evidence supporting microlending programs targeting women effectively demonstrates the contribution of women in poverty reduction schemes (Khandker, 1998; Daley-Harris, 2006).

Based on Ghana’s 2000 Census, females constitute 51 percent of the country’s population (CIA World Fact book, 2007). Despite their majority status, Ghanaian women disproportionately remain economically disadvantaged. Public and private sector organizations underrepresent women’s contributions to the country in economic, agricultural, social, political, or security arenas. Although women are the major agricultural producers, they predominate in the informal market system. They are profoundly affected by

conflict and displacement and are at the greatest risk of HIV/AIDS (New Agriculturalist, 2004). The complexity of forces working against poor women is profound. Traditional sociocultural constraints have long limited women’s participation in the

economy. Women's lack of access to resources are now coupled with international issues of debt and global trade. At the bottom of the economic rung, women in Ghana continue to shoulder the burden of family during

economic discontinuity. By implication, persistent poverty and the underdevelopment of women’s security impact the development of the nation.

The 1997 United Nations Microcredit Summit spoke directly to the plight of those most vulnerable to conditions of persistent poverty and their inextricable link to global security. A sustainable future for many people living in absolute poverty is a prerequisite for global peace and development (UN/UNESCO, 1997). The report further suggested that for maximum impact and sustainability, achievements in the field of microfinance will have to be matched by appropriate social services, especially education and health care (UN/UNESCO, 1997).

Mark Malloch Brown, Administrator of the United Nations Development Program

(UNDP), explained:

Microfinance is much more than simply an income-generating tool. By directly empowering poor people,

particularly women, it has become one of the key driving mechanisms towards meeting the Millennium

Development Goals, specifically, the overarching target of halving extreme poverty and hunger by 2015 (U.N.,

2005).

Creating Greater Equity

Through ongoing fundraising activities, donations, and competitive grants, the Zonta Club of Lansing

supports

revolving microcredit loan programs for the rural consortium and an urban cottage-industry skill program. Microloans for the three district rural consortium

average $1350 U.S. Revolving funding for the urban initiative

average $400 U.S.

These microloan initiatives partner with the Ghanaian government and private sector sources to provide capacity-building services for the target population. The Ghana Ministry of Rural Development & Environment provides outreach and technical assistance to rural communities through the work of rural development

officer, who facilitate the microcredit initiatives for their

assigned district. Similar to U.S. extension officers, rural

development officers support economic and social development activities in the local community.

Development officers oversee each local district microloan

initiative and meet quarterly to share programming and implementation strategies.

The rural consortium program uses a revolving microloan scheme. Loans

were provided to a collective of 15-20 women in each of the three districts. A total of 50 women from the three rural districts were included in the first round. As loans

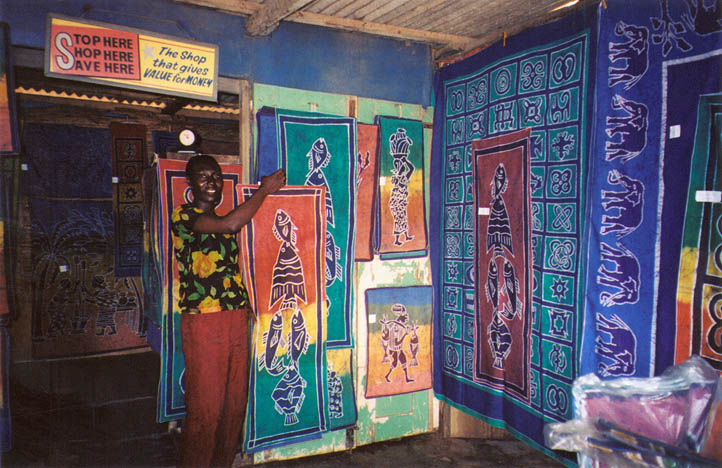

were repaid with a small amount of interest, loans were then extended to another 15-20 women in each district. Collectively, participant groups determine how loans will be used to support a particular entrepreneurial venture. Such ventures have included poultry production, yam farming, bread making, tie-dye cloth production, basket weaving, and animal husbandry. Participants also determine the repayment schedule for recycling loans.

Figure 1. Tie-dye process

Figure 2. Tie-dye art

Figure 3. Goat farm initiative

Development officers organize entrepreneurial capacity-building modalities, including instruction on basic business plan design, marketing strategies, and bookkeeping techniques. Self-esteem and leadership training sessions

are core features of regular meetings. Participants take turns chairing and facilitating local meetings.

The centerpiece of the urban microcredit program is its focus

on technical skill development. The owner of a cottage industry/home-based tailoring and seamstress business

operates in Accra’s urban center.

At any given time, between 12-15 employees perform a broad range of sewing-related operations. The owner

used her microloan to

purchase of an industrial sewing machine. This specialized

machine afforded her the opportunity to markedly expand the range of

services the business could offer, thereby translating increased

services into increased profits.

Moreover, this business woman extended the industrial sewing

machine training to her employees and eventually included training opportunities

for local women seeking to acquire a new skill set. As many poor women have virtually no access to an industrial sewing machine, opportunities to learn skills associated with the machine are almost non-existent.

The urban entrepreneur used networking as her vehicle to recruit

local women She also used employees to identify local seamstresses

interested in expanding their skill sets. Ultimately, her major

challenge was accommodating increasing numbers of women seeking

training to expand their employment opportunities. The enhanced equipment had a significant impact on the owner’s business, fostering an increase in productivity, including expanding the range of products she

offered. Increased productivity translated into increased profit, allowing her to pay off her loan of $400 U.S., with required interest, in advance of the due date.

A government development officer is not assigned to the urban initiative. Instead, this established business owner

involves other local business women to share their business

experiences by providing small business basic operation and managed

skills. Training sessions also include a focus on personal

development/empowerment, self-esteem, women's health and safety, and

other issues related to advancing the rights of women. The sessions

have produced exceptional results, including establishing a viable networking system for program participants. Quality training, combined with networking opportunities,

resulted in related, technical skilled employment for several program participants.

Technical assistance support for urban program participants

focused on building skill and proficiency in operating industrial

sewing machines. Participants received support with introductory

business practices and procedures, including instruction in

developing business plans, basic record keeping, inventory

processes, sales strategies, and time management.

Program Governance

A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) frames operating processes for the International Women’s MicroCredit Loan Program. The MOU

between the Zonta Club of Lansing and the designated Ghanaian microcredit loan

recipients outlines the terms of agreement, including proposed program goals, lending guidelines, program loan amount and interest rate, loan disbursement procedures, repayment instructions, expectations for program monitoring, and fiscal oversight. Zonta Club of Lansing

utilizes the

services of an in-country NGO (Non-Governmental Organization)

monitor to facilitate loan disbursement payments and to provide project oversight and coordination, fiscal management, and

project documentation.

Establishing consistent in-country and international communication is essential to operating an international endeavor. Program monitoring, especially monitoring a new initiative, is a time-intensive process. The Club’s initial planning underestimated the time required for appropriate monitoring processes.

By design, the three rural programs are located in districts in different parts of the country. The urban initiative

is located in a part of metropolitan Accra, different from the monitor’s base location. Distance between sites can be a challenge. In Ghana, not unlike roads in many developing nations in Sub-Saharan Africa, accessible

intrastate travel lacks consistency. Unpaved road travel often adds both time and cost to a travel

itinerary, and travel costs increase when overnight lodging and meals are included.

The Zonta Club of Lansing grossly underestimated the12-month budget to support

program monitoring activities. The Club encountered a substantive disconnect between monitor tasks, as outlined in the MOU, and resources allocated to successfully accomplish

those tasks. For example, the MOU provided a total of $60 to support travel for three meetings. However, the MOU did not allocate

sufficient funding to support travel for the site visits called for

as part of program oversight and formative/summative assessment. Fortunately, the

initial monitoring activities were able to continue due to increased

in-kind contributions on the part of the NGO partner, the May Day

Rural Project.

Year 01 Program Highlights

The International Women’s MicroCredit Loan Development Program marked completion of its first year of operation in June 2007. By

then all loans were paid in full, including the required 4.5 percent interest.

These repayment results are consistent with the growing body of

research documenting the fact that microcredit loan recipients are

indeed credit-worthy and tend to repay their loans at rates higher

than repayment reported by commercial banks (Smith and Thruman, 2008; Khandker, 1998). The success rate for IWMC loan repayment

more than substantiated the Club's decision to enter into a year-02 funding cycle.

Highlights of first year programming also confirmed the effectiveness of microcredit lending as a viable strategy for poverty reduction and the empowerment of women. In great measure, the effectiveness of first-year programming was attributable to a program design emphasizing collaboration, shared learning, and community participants serving as major resource providers.

Establishing self-esteem training for women, especially marginalized women having little experience or opportunity to affect a community improvement initiative,

offered evidence of success in both the rural consortium and the urban

district. Utilizing the expertise of rural community development officers to provide technical assistance and to facilitate loan program operations

proved to be an invaluable asset. Among the many contributions of the rural development officers was their ability to successfully promote leadership.

Looking forward, both the rural and urban cohort programs addressed issues of sustainability and scale-up. Participants were exceptionally interested in exploring

strategies to increase the numbers of women who might participate in the respective

microloan programs. Both groups strongly supported personal development

training as a major component of microcredit programming. Moreover, participants identified the dual emphasis of

economic and personal development as a potentially effective strategy to use with young girls migrating from rural areas into urban centers.

Like many young people throughout the developing world, Ghanaian youth and young adults are migrating from rural areas to urban centers

in search of an opportunity to improve their economic condition. Cities can indeed mean places of hope and growth. For increasing numbers of Ghanaian migrants, the cities

instead offer pollution, disease, and insecurity. Unfortunately, their search for the persistently illusive promise of employment most often yields little in the way of economic advancement.

Migration to Ghana’s urban centers is placing unprecedented stress on the social fabric and economic infrastructure of the country’s central cities. Female migration to urban areas, in far too many cases, places these young women at risk for physical and sexual assault and exploitation. Because most female urban migrants have little or no formal education, they are more at risk for underemployment/unemployment (World Watch Institute, 2007).

A number of participants volunteered to work on plans to identify a cohort of young women from rural areas who have migrated to cities.

Suggestions included targeted programming to recruit girls and encourage them to return to their rural community

by offering girls a chance to participate in capacity-building microloan

initiatives. This collective problem-solving strategy speaks volumes for participants’ level of commitment to breaking the cycle of

poverty.

A common theme emerged as women addressed the impact of poverty on self-esteem and empowerment. Specifically, women were concerned with developing interventions to prevent the next generation of girls growing up in the depths of poverty. Across the rural and the urban programs, participants

identified a need to significantly increase opportunities for girls to enter and complete secondary and university education.

The Zonta Club of Lansing has continued to follow the progress of the Ghana Zonta

Clubs' women’s shelter project. As part of the Lansing Club's

continuing support and fundraising efforts, the Club is exploring

possible ways to implement an entrepreneurial initiative for shelter residents.

Recommendations

The IWMC continues to be a catalyst for generating dialogue about refining strategies to improve the status of women, especially women in developing countries. The initiative benefits from a wide range of stakeholder and partnership input. In part, the following recommendations reflect this shared learning. Selected recommendations for consideration include:

- Seek grant funding to support the continuing development of the Ghana microcredit loan/service initiatives incorporating a broader perspective of poverty reduction

- Systematically study patterns of program progress and challenges to continuously improve program operations

- Expand partnerships with university, public/private sector efforts, and others to support and improve service delivery

- Create communities of researchers working toward measurable outcomes

- Involve university partners to develop course work in microcredit

- Develop comprehensive service learning/study abroad programs

- Expand partnerships/share learning with Zonta Clubs and

community/volunteer programs participating in microfunding initiatives

- Develop appropriate assessment measurements

- Document and evaluate program processes

Lessons Learned/Continuing Challenges

The International Women’s MicroCredit Loan Development Program entered into a collaborative effort to

provide women in a developing country an economic advantage outside

of the traditional banking system. The initiative experienced significant achievements,

in great measure attributable to the laudatory effort and commitment of program participants and the generosity of the numerous donors who believed in the potential of this

small effort. This experience offers endless opportunity for continuing development, partnership prospects, scale-up, and continuous improvement. Among the myriad of lessons learned, the following may be the most prominent:

- Effective in-country and U.S. partnerships are critical to addressing a broadened definition of poverty and its disproportionate impact on women.

- Site visits should be incorporated as a component of international efforts dependent upon grant funding. Grantors seek documentation and verification of initial efforts.

- Participant empowerment is an absolute lynchpin of the program. Motivation, support, and shared learning among beneficiaries in both cohorts were exceptional and should be systematically studied as a core feature of poverty alleviation strategies.

- Although the contributions of the program monitor were exceptional, such efforts require in-country staff support. Regular, continuing programmatic support is required to address routine program issues.

Conclusion

This narrative stresses the importance of advocacy on behalf of those at greatest risk—especially poor women. Clearly, there is need to promote the role of women in social and economic development by reinforcing their capacity and their access to formal education and training. Developing revenue-generating opportunities for women by having access to credit increases their life

chances. At the same time, supporting women’s equitable participation

in economic development reduces national poverty rates.

The Zonta Club of Lansing’s MicroCredit Loan Development Program offers substantive evidence that small amounts of monetary lending have even greater impact when accompanied by complementary services such as empowerment, leadership training, and active citizen participation. Critical to success of current and future programming is the set of guiding principles that promotes human security and social justice.

References

Adablah, C. (2004). “Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy: Institutional Framework for Employment Monitoring. Paper presented at the Joint ILO/UNDP (International Labor Organization/United Nations Development Program) Mission Conference on Elaborating Employment Strategies within the Context of the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy. November 29-December 5, 2003 and April 27-May 7, 2004, Ghana.

Central Intelligence Agency (2007). The World Fact Book. Retrieved November 5, 2007, from https://www.cia.gov

Daley-Harris, S. (2006). More Pathways Out of Poverty: Innovations in Microfinance for the Poorest Families. CT: Kumarian Press.

Republic of Ghana (2003). Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy. Accra: Ghana Government Printing.

Grameen Communications. A Short History of the Grameen Bank (2002). Retrieved June 25, 2007, from

http://www.grameen-info.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=19&Itemid=114

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). Rural Poverty in Ghana. Retrieved May 10, 2007, from http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org

Khandker, S. (1998). Fighting Poverty with Microcredit: Experience in Bangladesh. NY: Oxford University Press.

Mjos,O. D. The Nobel Prize Presentation Speech, Retrieved February 14, 2007, from http://nobelprize.org

Ministry of Women & Children’s Affairs (2001). National Gender & Children Policy. Republic of Ghana: Ghana Printing Office.

Montgomery, Mark, Stren, R., Cohen, M., & Reed, H. (eds.) (2003). Cities Transformed: Demographic Change and Its Implication in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

New Agriculturalist (2004). Country Profile Ghana. Retrieved August 10, 2007, from

http://www.new-ag.info/04-3/countryp.html

Smith, P., & Thurman, E. (2007). A Billion Bootstraps: Microcredit, Barefoot

Banking and the Business Solution for Ending Poverty. NY: McGraw-Hill.

Rhyne, E. (2001). Mainstreaming Microfinance: How Lending to the Poor Began,

Grew and Came of Age in Bolivia. CT: Kumarian.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) (2003). State of World Population 2003. Making 1 Billion Count, NY: United Nations.

United Nations (2005). U.N.Resolution: International Year of Microcredit 2005,

A/RES/53/197, NY: U.N. Department of Economic & Social Affairs (DESA).

United Nations Educational, Scientific & Cultural Organization (1997). UNESCO

Microcredit Summit Position Paper (CAB-97/WS/2), February 2-4, 1997.NY: UNESCO.

van Vilet, W. (2002). Cities in a Globalizing World: From Engines of Growth to Agents of Change. Journal of Environment and Urbanization, 14, 31-40.

World Bank (2007). Global Monitoring Report 2007: Confronting the Challenge of

Gender Equality & Fragile States. NY: Oxford University Press.

World Bank. (2000). Entering the 21st Century: World Development 1999-2000.

NY: Oxford University Press, 2000.

World Watch Institute (2007). State of the World 2007: Our Urban Future. NY: W.W. North.

Wright, G. A. (2000). Microfinance Systems: Designing Quality Financial Services for the Poor. NY: Zed Books Ltd.

Yunus, M. (2003). Banker to the Poor: Micro-Lending and the Battle Against World Poverty. NY: Public Affairs.

|